Download documents and transcripts

Teachers' notes

The purpose of this document collection is to make available to teachers and students a wide selection of documents relating to the suffragette movement. The sources include material from the Home Office, Metropolitan Police and prison files, the Women’s Social and Political Union office (W.S.P.U.) which were used as exhibits in the trial of Emmeline Pankhurst and other leaders, including their correspondence and the Suffragette newspaper. We hope that such a collection will offer teachers the flexibility to develop their own approaches and questions and differentiate student tasks. All documents are provided with transcripts. Please note that in many cases we have displayed the whole document and highlighted the extract we have chosen to transcribe. These records support numerous lines enquiry on a range of significant themes. Here are some suggestions:

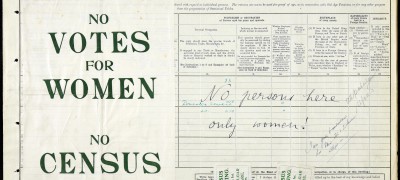

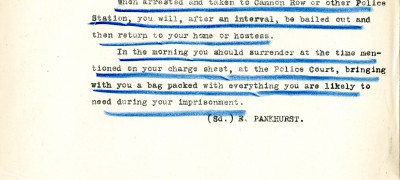

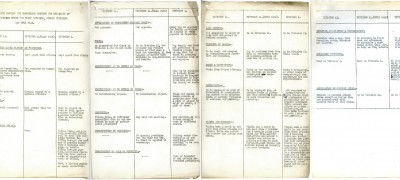

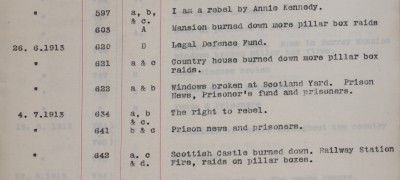

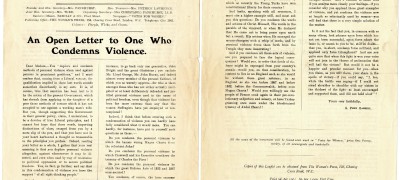

- What tactics and types of protest were employed by the movement to draw attention to their cause? [sources covering: marches; attacks on pillar-boxes; response to imprisonment; hunger strikes; petitions; window smashing; marches; census boycott]

- How successful was the Suffragette movement in terms of marketing its campaign? [Sources covering: membership; organisation; logos, banners; newspapers, posters, hand bills]

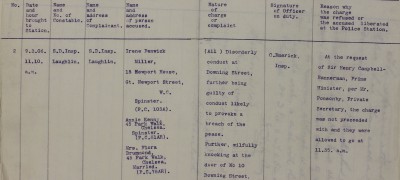

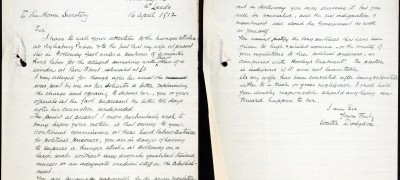

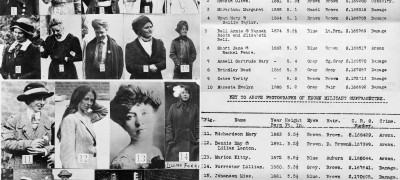

- How did the government respond to the movement? [Sources including: prison records, legislation, police reports, newspaper articles]

- What methods were used by the police to detect suffragette activities? [sources: surveillance, cameras, finger printing]

- How did some politicians view the movement? [Sources on Asquith, Keir Hardy]

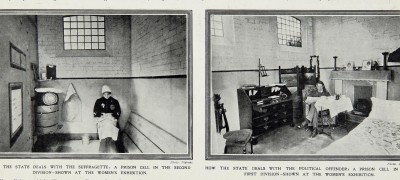

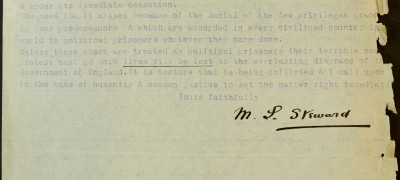

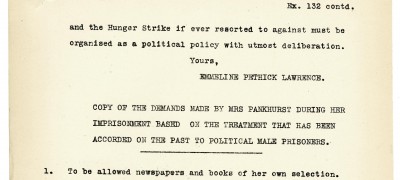

- Why was it so important for the suffragettes to be viewed as political prisoners? [sources: photographs, prison document on treatment of prisoners, leaders’ statements]

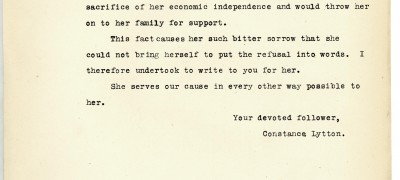

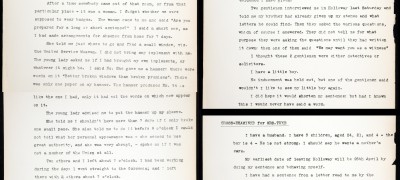

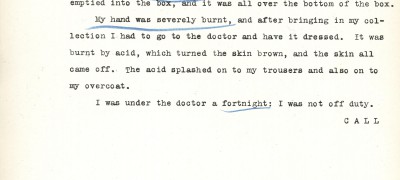

- What personal stories of women involved in the movement are evident in these records? How do they explain women’s motivation for becoming involved and the sacrifices they were prepared to make? [Sources: Annie Kenney, Lillian Ball, Mary Richardson, Sylvia Pankhurst, Christabel & Emily Pankhurst, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, May Billington, Lady Constance Lytton]

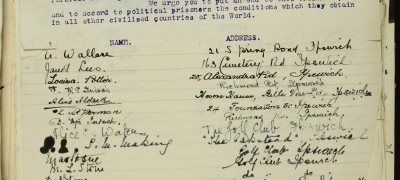

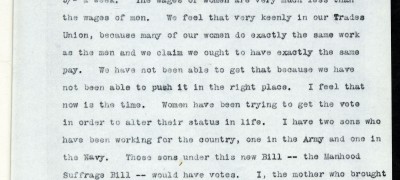

- What was the degree of support for the movement amongst the public? Did it cross all classes? [Sources: working class female workers participation, middle class female supporters]

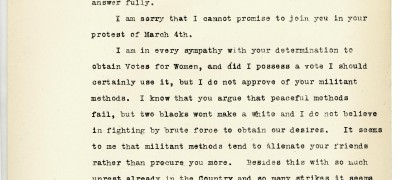

- How did men support the movement? [Sources: letters from men, male protest, men’s suffrage societies]

- How successful was the WSPU by 1914?

- Have any of the documents in this selection surprised you, or altered your original perception of the suffragette movement?

It is important that students recognise that the same document can serve as evidence for more than one line of enquiry. Encourage students to interpret the records, spot inferences and try and detect any unwitting testimony. Here are some general guidance questions to help them evaluate and understand documents. Teachers may wish to print these out and discuss with the students before looking at the material.

Key stage 5 teachers could break their class up into groups and ask students to feed back on the different documents and/or annotate them on a white board. Students can discuss their interpretations having analysed the sources. This could generate discussion about the nature of evidence and how it can be used to construct different interpretations of the past.

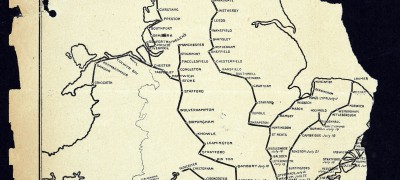

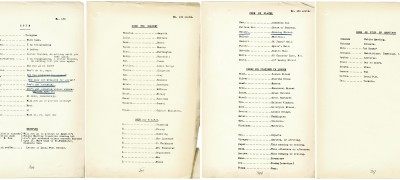

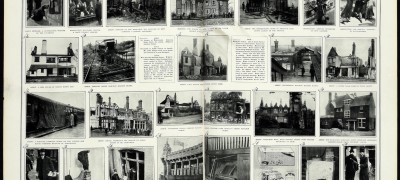

Key stage 1 & 3 teachers may prefer to work with selected documents or extracts from the collection and/or use the material for their own research. The material from the ‘Illustrated London News’ is highly accessible, in particular the source entitled: ‘From pavement-chalking to arson, window-breaking and bombing: the progress of Militant Suffragism’, 24 May 1913. This contains over 25 photographs and a chronology. Also ‘the Women’s Suffrage Pilgrimage map’ which shows the extent of national protest and peaceful campaign methods is an interesting visual source. With this, we have made available, an interactive map with photographs to compliment it. Again the samples of suffragette ‘message codes’ used to conceal their activities are provided in this collection. Younger pupils could be tasked to write their own messages using the code words. Emily Davison is referred to in the Key Stage 1 curriculum. We provide a source describing how she hid overnight in Parliament.

The students’ interpretations of the documents could be captured using a variety of approaches:

- Write a chapter for designed for a school history text book

- Create a brochure for an exhibition to commemorate the struggle for the vote

- Write a report/newspaper feature on particular event

- Hold a debate on the case for/against the different tactics used by suffragettes or debate police/authorities responses’ to the campaign.

- PowerPoint presentations on different aspects of the campaign

- Create a short video documentary on a suffragette

- podcasts

- blogs

- web pages

- Create an annotated timeline of events based on the documents

Finally, students could compare how the suffragette movement has been analysed and described in a number of published history textbooks in light of these original documents. They could look at further primary documents provided in The National Archives education related resources on this webpage:

Suffragettes on Film

This film resources has several clips of archive footage on the suffragettes

Suffrage Tales

View the animated film produced as result of The National Archives Film Project for

16-19 year olds in 2017.The students’ work was inspired by some of the original documents available in this collection

Quiz yourself on: the Suffragettes

How much do you know about the Suffragettes and women’s right to vote?

Connections to the curriculum

Key stage 5

- AQA – A Level History: Britain in Transition 1906-1957: The Liberal Crisis 1906-1914.

- Edexcel – A Level History: Protest, Agitation and Parliamentary Reform in Britain c1780-1928: The Women’s Social and Political Union.

- OCR – A Level History: England and a New Century c1900-1918: Political issues: the issue of women’s suffrage 1906-1914.

Key stage 3

Challenges for Britain, Europe and the wider world 1901 to the present day: Women’s Suffrage

Key stage 1

Aspect of history: Subject knowledge, significant individual

Introduction

Christabel Pankhurst, twenty-three years-old, was impatient for change: ‘the vote question must be settled. Mine was the third generation of women to claim the vote and the vote must now be obtained. To go on helplessly pleading was undignified. Strong and urgent demand was needed. Success must be hastened.’

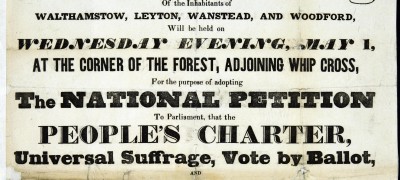

On 10th October 1903 the Women’s Social and Political Union, a new organisation demanding Votes for Women, pushed its way noisily onto the women’s suffrage scene. Until then the effort was led by Mrs Millicent Fawcett and her National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies, a movement founded in the 1860s. At Mrs Emmeline Pankhurst’s home in Manchester, the new Union announced its modernity with the three-word slogan: ‘Deeds Not Words.’ Mrs Pankhurst’s eldest daughter Christabel became the strategist for the movement. The campaign was a response to the Great Reform Act of 1832, which had enfranchised only ‘male persons’ with property, excluding, by definition, all women.

The W.S.P.U. demonstrated their agitprop approach in the first of many militant protests: Christabel, and Annie Kenney, a mill girl from Oldham, chose a meeting held by Liberal politicians Winston Churchill and Sir Edward Grey, in Manchester on 13th October 1905. As result of their noisy interruptions and persistent questions, they were ejected and continued to protest outside and were later sent to Strangeways Prison. Today we might now describe their actions as controversial, but at the time they were found deeply troubling and unfeminine. The slogan ‘Deeds Not Words’ had become a reality, and a precedent for their entire campaign.

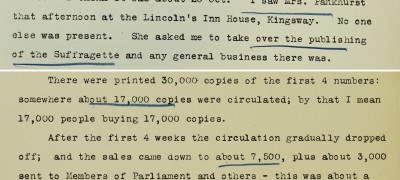

This public disobedience earned the W.S.P.U. a derogatory nickname, ‘Suffragettes,’ coined by a ‘Daily Mail‘ reporter in January 1906. The ‘Suffragettes’ adopted the term and used it for their militant newspaper, ‘The Suffragette’, launched in the summer of 1912.

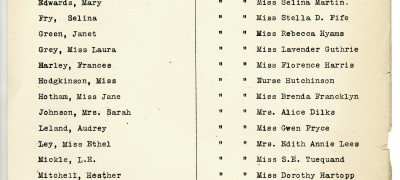

The W.S.P.U. moved to London in 1906, and opened a national headquarters at 4, Clement’s Inn. Frederick and Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence funded the office accommodation in the early days. Emmeline’s fundraising and Frederick’s expertise as a barrister initiated a formidable campaign, which has never been seen before or since. By the end 1912, fifty-eight branches existed across the country recruiting women from all backgrounds and occupations. Membership lists were not kept in case of police raids on their premises. Donors listed in their weekly newspaper ‘Votes for Women’ showed that thousands of women supported the campaign financially and actively.

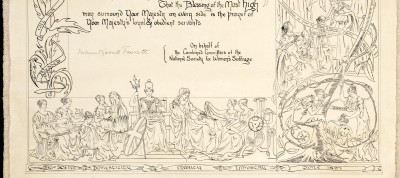

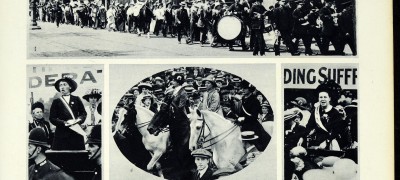

Nowadays we take marketing for granted, but it was first used politically by the W.S.P.U, who created their campaign as a brand. There were well-designed logos, stylish exhibitions, spectacular processions and meetings in London and the major cities. Special colours represented the movement, purple, white and green for freedom, purity, and hope respectively. Supporters wore the colours and they were used on badges, bicycles, chocolate bars, cakes, jewelry and even a motor-car.

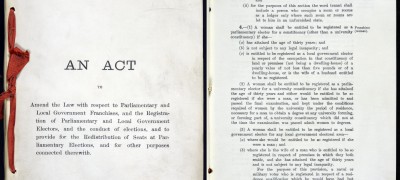

Faced with determined opposition from many politicians, the press and the public (including women), Keir Hardie, M.P. (Independent Labour Party) was a good political friend to the women’s suffrage campaigners. While Liberal politicians consistently voted in support of the Conciliation Bills to grant a measure of women’s suffrage in 1910, 1911 and 1912, their wishes were crushed by the anti-women’s suffrage Prime Minister Herbert Asquith and others who refused to steer a Bill through Parliament. The collapse of the 1912 Conciliation Bill was the trigger which propelled the W.S.P.U. into sanctioning extreme militancy which marked the final two years of the campaign until the outbreak of the First World War.

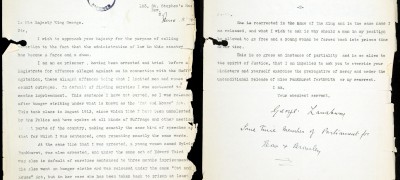

The two men’s organizations which worked for votes for women were the Men’s League for Women’s Suffrage, founded in 1907, and the Men’s Political Union for Women’s Enfranchisement of 1910. Many men supported their wives, sisters and girlfriends, although most men did not. Those who did paid a heavy price for being ‘sex traitors’ and suffered violence whilst offering protection at public meetings, and lost their reputations or jobs.

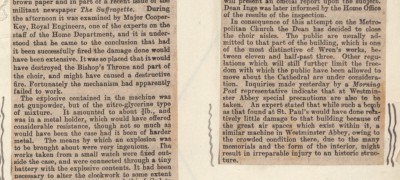

Until the increased militancy of 1912 the moderate suffragists – the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies – and the militant suffragettes worked together. Members of both wore each-others’ badges, and joined the same marches. They all handed out leaflets about enfranchisement of women, canvassed for the private members’ bill and sold newspapers. Yet, these documents reveal that the suffragettes went further: they attempted to enter the House of Commons; heckled meetings; blew up pillar-boxes; smashed windows; burnt down empty buildings and attacked works of art.

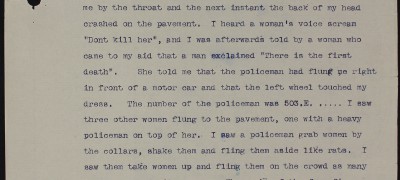

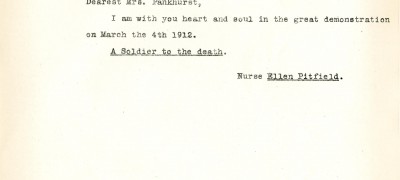

By the summer of 1914 the positions of suffragettes and Liberal government were deeply entrenched: the W.S.P.U. was determined to force the government to give women the vote, and the establishment equally stubbornly refused to comply. Over a thousand British suffragettes had acquired a criminal record and many were imprisoned for demanding the vote. These records show that suffragettes were denied the status of political prisoners and treated as ‘common criminals’. In protest many went on hunger-strike and were force fed with terrible consequences for their health. The W.S.P.U. awarded women who experienced this torture with ‘For Valour’ medals: ‘in recognition of a gallant action, whereby through endurance to the last extremity of hunger and hardship, a great principle of political justice was vindicated.’

Dr. Diane Atkinson

‘Rise Up Women! : The Remarkable Lives of the Suffragettes’ (Published by Bloomsbury, February 2018)

External links

BBC archive of historic broadcast interviews with Suffragettes

BBC News story article on the struggle for the vote

Explore London School of Economics fascinating online collection on women’s suffrage

Some excellent resources from Parliament.uk to support political education

Back to top

Cats and mice

What tactics were used by suffragettes, police and government?Spotlight On: Copyright Office

Collections expert Katherine Howells introduces two records from the copyright office collection.

Suffrage Tales

What would you do?Suffragettes: Outrage at Kew

What's the story?Quiz yourself on: the Suffragettes

How much do you know about the Suffragettes and women’s right to vote?