Download documents and transcripts

Teachers' notes

The purpose of this two part document collection is to allow students and teachers to develop their own questions and lines of historical enquiry on various social, economic and political aspects of 1920s Britain. The document icons are labelled so it is possible to detect key themes at a glance and they are arranged in chronological order.

In this part (part 1) the themes covered include:

- The economy: Geddes Axe, the Gold Standard 1925, unemployment

- Industrial unrest: General Strike, Hunger Marches 1927 & 1929

- First Labour Government 1924

- Communist Party of Great Britain

- Transport: motors cars and trains

- Role of women

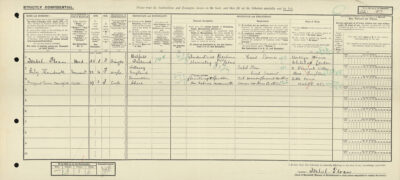

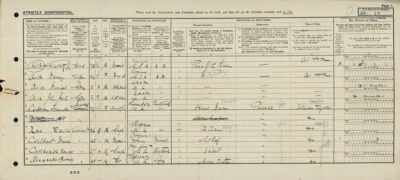

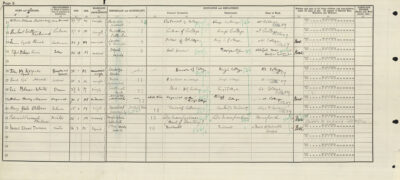

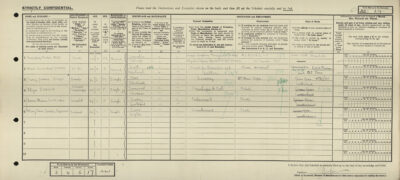

- 1921 Census entries for significant people in the decade

Please also note that in some cases, linked sources on the same same topic appear in the same popup window so it is necessary to scroll from side to side to explore them in detail.

Students could work with a group of sources or source type on a certain theme or linked themes. The documents should offer them a chance to develop their powers of evaluation and analysis and support their course work. Alternatively, teachers may wish to use the collection to develop their own resources or encourage students to ‘curate’ their own ‘exhibition’ of the most significant sources on the topic. More documents can be found in 1920s Britain (Part 2) Decade of conflict, realignment and change? Students could also use more documents from our Cabinet Papers website.

Finally, there is an opportunity to consider film sources as interpretations of these events in relation to the documents by following the links to Pathé and the BFI provided here.

Connections to the curriculum

These documents can be used to support any of the exam board specifications covering the political, social and cultural aspects of 20th century British history, for example:

AQA: GCE History

Wars and welfare: Britain in transition 1906-1957

Society in crisis 1906-1929

Edexcel: GCE History

Study in Breath: Britain Transformed 1918-1997

OCR: GCE History

Period study: Britain 1900-1951

Introduction

Professor Keith Laybourn, Diamond Jubilee Professor of the University of Huddersfield

The 1920s saw a rapid transformation in British society, almost to the point of fundamentally transforming the basis of its political, economic and social organisation even though there remained many areas of resistance to change: the Labour Party replaced the Liberal Party as the progressive party in British politics, women got the vote, and the car transformed the transport of the age as well as policing and social relations in British society. Such change was partly the result of the First World War but also the consequence of social and technical changes in British society which often pre-dated the War but which became amplified in the 1920s by the impact of war.

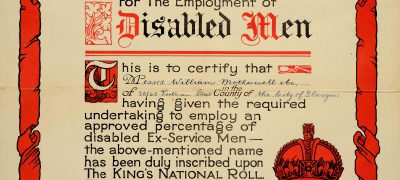

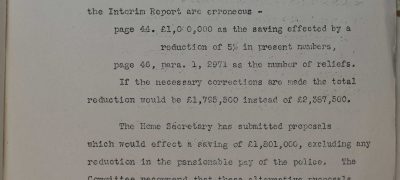

The First World War certainly exerted a major impact upon the British economy. The loss of foreign markets for the staple industries of Britain – coal, iron and steel, shipbuilding and cotton led to a rapid rise in unemployment. Post-war governments were immediately faced with the return of soldiers and ex-servicemen and applied the Treasury Agreement with the Trade Unions, made in 1915, that allowed service-men to return to their own jobs in some industries at the expense of women who had replaced them for the duration. A Ministry of Labour scheme to return 50,000 ex-service men to work failed as only 202 men were found jobs and 24,000 of them in the Building and Allied trades were still receiving unemployment benefits in 1921. Therefore, governments widened insurance legislation to provide benefits for the unemployed and offered relief work, trying to avoid forcing the unemployed into the poor houses. There a National Scheme for the Employment of Disabled Men. Yet, governments did little to tackle the underlying problem of industrial decline. Committed as they were to deflating the economy to strengthen the pound in the hope of returning to the Gold Standard, the symbol of international free trade that had made Britain great in the nineteenth century before being suspended in the War, successive governments failed to tackle unemployment. The Geddes Report or Geddes Axe of 1921/2, which brought cuts to government departments, worsened to chances of economic growth. Agitation from the unemployed was led by the Communist Party of Great Britain, formed in 1920, and the National Unemployed Workers (Committee) Movement (NUWM) formed in 1921.

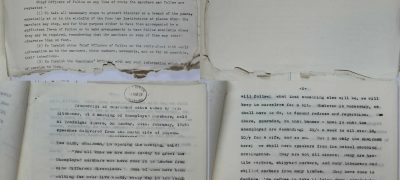

With Communist leader Walter Hannington, the NUWM organised many unemployed, and particularly ex-servicemen in protests against the inadequate unemployment benefits. The miners organised their own protest march. The Miners’ March to London from Wales in November 1927 was supported by the NUWM, communist and socialist groups. The NUWM’S 1929 Hunger March, organised in January-February, saw marchers from nine areas of Britain march on London demanding better unemployment benefits and work for the unemployed.

War had led to Britain going off the gold standard and free trade, the hallmark of nineteenth-century Victorian economic prosperity. It was restored to the pre-war parity of $ 4.86 by Winston Churchill in 1925 when its value was only $4.40 to the £, hence British goods immediately became 10 per cent more expensive to foreign buyers. This added to economic decline and unemployment only to be heightened by the Wall Street Crash in 1929.

The continued policy of deflation, consequent wage reductions and unemployment, lead to strikes and major industrial unrest. The coal miners struck unsuccessfully against wage reductions in 1921, largely because the Miners’ Federation of Great Britain was not supported by the National Union of Railwaymen and the National Transport Workers’ Federation or ‘Triple Alliance.’

When the return to the Gold Standard led to further demands for reduced wages, the resistance of the miners in 1925 eventually led to the General Strike of 1926 when about 1,500,000 trade unionists came out in support of about 800,000 miners who were faced with wage reductions of 10 per cent and an increase in working hours. Although the General Strike failed, lasting only between the 3 and 12 May, employers were afterwards more reluctant to try to reduce the wages of their employees.

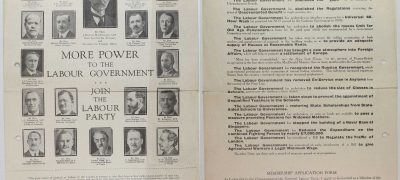

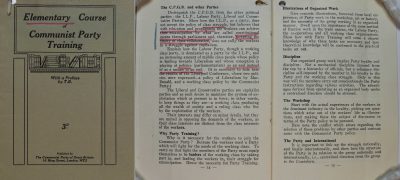

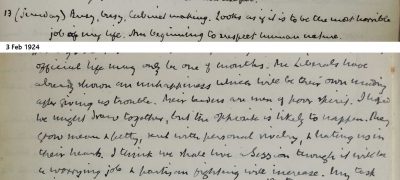

Politics in Britain changed because of the war. It divided the Liberal Party in 1916, which led to David Lloyd George to replacing H.H. Asquith as head of a wartime coalition government and leader of peacetime coalition government (1918-1922). By the 1924 general election the Liberals were reduced to 40 MPs, a sharp decline from the 400 returned at the 1906 general election. The Labour Party, now with its socialist constitution of 1918, emerged as the progressive party in British politics, forming minority governments under James Ramsay MacDonald in 1924 and 1929. In 1924 King George V wondered ‘what grandmama [Queen Victoria] would have thought’ at the prospect of a Labour government, even if, as Tom Jones, the Assistant-Secretary to the Cabinet had written that it was ‘Pale pink rather than Turkey Red’. But times had changed. The 1918 Franchise Act had enfranchised all men over the age of 21 and many propertied women of 30 and over, and the wider electorate favoured the Labour Party, endorsed the Conservative Party as the party of the nation, and left the Liberal Party in sharp decline. The minority Labour government formed in 1924 was supported by the Liberal Party but was short-lived because the Liberals withdrew their support owing to its commitment to trading with Russia. Given Labour’s weak political position it would probably, in any case, have lost the 1924 general election but the appearance of the infamous Zinoviev (Zinofieff) Letter, indicating the intention of the Communist International (Comintern) to infiltrate the Labour Party and to use it as a means of bringing about revolutionary change in Britain may have ensured this. It is now regarded as a political spoof to discredit the Labour Party on the eve of a general election. At this time there had been enormous concern in Britain about the Russian Revolutions of 1917, and the formation of the Communist International (Comintern) in 1919 to wage world revolution for Marxism. From the beginning the British Government, through the Home Office MI5, M16, and Special Branch, had kept a close watch upon the revolutionary Communist Party of Great Britain, which had produced an ‘Elementary Course of Communist Party Training’, rejecting parliamentary and constitutional changes of the Labour Party, the Independent Labour Party, and other reformist socialist parties in Britain in favour of class conflict.

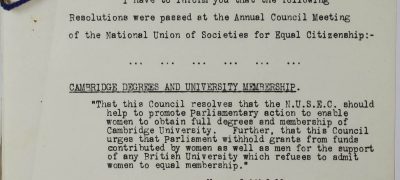

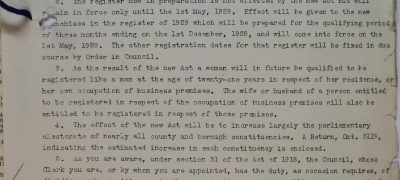

These broad realignments in British politics were a reflection of other social developments in British society. Women of property over 30 had gained the parliamentary vote in 1918, but that fight for female enfranchisement was not completed until the passing of the Franchise Act of 1928, that gave the vote to all women over 21. Other women’s issues came very much to the fore in the 1920s. The post-war neglect of widows was, for instance, rectified by the Baldwin Conservative government in 1925 with a ten-shilling pension and additional allowances for children. However, political and social equality for women came slowly and grudgingly. There were never more than eight women in the House of Commons at one time in the 1920s, and only Margaret Bondfield became a female member of the Cabinet, appointed as Minister of Labour in the second Labour government of 1929-1931.

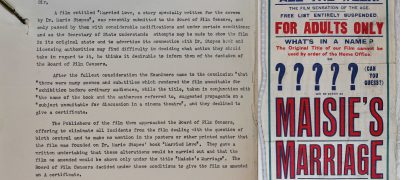

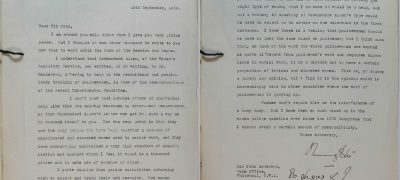

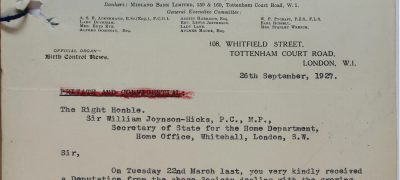

British society was still very much reluctant to offer economic and social equality to women. Marie Stopes was, indeed, among a number of women activists who fought for better birth control options for women, opening clinics in the East End of London for working-class women, and encouraging the formation of the 66 birth control organisations which became the basis of the Family Planning Association in 1930. Throughout the 1920s Stopes had sought to advertise information about birth control and had, for instance, produced a silent film drama of her book ‘Married Love’. It was refused a certificate from the Board of Film Censors in 1923 until the film publishers undertook to remove ‘all incidents from the film, dealing with the question of birth control, and the film was only allowed to be shown subject to the elimination of its main message, and shown, in a highly censored way as ‘Maisie’s Marriage’, advertised as ‘The film they didn’t want you to see in 1923.’ Stopes also campaigned, on behalf of the Society for Constructive Birth Control and Racial Progress, against the ‘growing scandal of the Abortion-mongers and Abortifacient Advertisements’ who were endangering the lives of women wanted terminations. This was set against a background in which the Maternity and Infant Welfare Centres, set up by local authorities and government in the early 1920s should only deal with expectant or nursing mothers and not with those wanting birth control.

British society remained intensely gender and class ridden throughout the 1920s. Women had only slowly, and prosaically, gained political rights in the 1920s and secured little in the way of equality of opportunity in employment and education. Even middle-class women seeking degrees at the older universities had to struggle to obtain equality of treatment and the National Union of Societies for Equal Citizenship at Cambridge and at other British universities. A Married Women’s Employment Bill was discussed, though not passed, in 1927, its aim being to prevent any Government and local authority from dismissing women on grounds of marriage or if about to be married.

External links

https://www.britishpathe.com/ – Explore archive footage relating to 1920s Britain.

https://www.screenonline.org.uk/film/id/1364849/index.html – Take a look at 1920s stars and feature films.

https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20s-people/20-people-of-the-20s/ – Read the stories of 20 different people who lived in the 1920s.

Back to top