20 People of the 20s is part of 20sPeople – our season to mark the release of the 1921 Census, connecting the 1920s and the 2020s. This story was researched by Roger, Principal Records Specialist, about his maternal great grandfather.

20 People of the 20s is part of 20sPeople – our season to mark the release of the 1921 Census, connecting the 1920s and the 2020s. This story was researched by Roger, Principal Records Specialist, about his maternal great grandfather.

The cotton weaver who became a soldier

An illustration of Ernest Butterworth, drawn from a photograph. By Sophie Glover.

Ernest Butterworth was born in 1877 to John and Susan Butterworth, the second youngest of seven children. The family lived in Wardle, a village in the valley of the River Roch, near Rochdale. His parents, like many in the area, worked in the cotton mills, his father as a cotton loom jobber (machine supervisor) and his mother a cotton weaver.

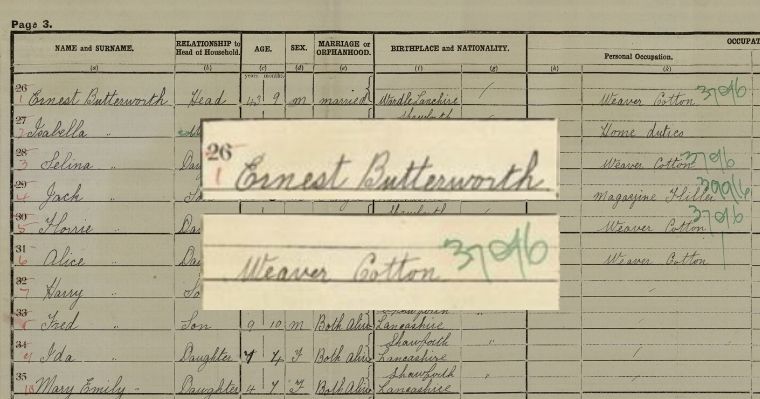

Rossendale towns, with a ready supply of fast flowing water, were ideal for cotton spinning and riverside mills were a common feature in the 19th century. At its peak, the area was producing some 68 million pounds (~31 million kilos) of yarn and 210 million yards (~192 million metres) of cloth each year. Ernest was himself a cotton operator by the age of 13. He was working as a stone quarry man by 1901, and the family had moved to Whitworth, a small town situated between Bacup and Rochdale. The 1911 Census records him as having returned to the occupation of cotton weaver, living in accommodation with only two rooms in the nearby village of Shawforth with a wife, Isabella, and five children. They would go on to have eight children in total.

Ernest Butterworth, in the 1921 Census

Working in the cotton mills was a dangerous, noisy and dirty experience, despite the introduction of various Factory Acts to improve conditions from the 1850s. The air in the mill had to be hot and humid to prevent the thread from breaking. Temperatures between 65-80 degrees Fahrenheit (18-27 degrees Celsius) and 85% humidity was normal, and the air in the mill would’ve been thick with cotton dust. Protective masks were not introduced until after the First World War, without which there was a high risk of developing breathing difficulties and lung diseases, as well as skin and eye infections and tuberculosis. Intense high noise levels could lead to deafness for those who worked in the mills over a long period of time. Typically, a mill worker could expect to work for 13 hours a day and six days a week.

Ernest in army uniform, after enlisting to fight in the First World War

These conditions may help to explain why Ernest, at the age of 38, decided to join the Army reserve on 12 December 1915. Recruitment had been high at the start of the war, before starting to fall by late 1915. At this time, it was unusual for someone to volunteer at such an age, and there is no evidence of previous army service in Ernest’s family history. Ernest was also relatively short at just 5 feet 4½ inches tall – perhaps not a typical build for a soldier.

His service records show that in April 1917 he was posted to France with the 16th Battalion of the Lancashire Fusiliers. He spent only two months in the trenches, before being hospitalized on 24 June 1917. The entry in the war diary, made on the previous day, read:

‘Relieved by 1st Battalion Black Watch and marched to Jean Bart Camp Coxyde-Bains, Belgium. The casualties during the tour of the trenches was 1 officer wounded, seven other ranks killed, thirteen other ranks injured’.

Ernest returned home in September 1917. He spent 66 days in hospital suffering from insomnia, sluggish reflexes, severe headaches and memory lapses, with ‘…no interest in his surroundings’. He was discharged on 20 September 1918, aged 41. His discharge notes state ‘feeblemindedness’ in the disease column.

Clearly traumatised by war, like so many men, Ernest never fully recovered. Many of the symptoms he experienced are symptomatic of ‘shell shock’.

In the 1921 Census, the family was still resident in Shawforth but had moved to a different home, Ernest’s widowed mother-in-law is now living with them. The 1921 Census, taken in June 1921, asked a specific question relating to the First World War. Children were asked whether their mother, father, or both were dead, so the Government could understand the impact of the war on society. Ernest was not one of the 700,000 men who died in the First World War, however he did pass away shortly after the Census was taken, on 27 December 1921 at just 44 years old.

Ernest’s youngest child was only four when he died. His widow, Isabella, would live for another 46 years, without remarrying. Ernest’s cause of death was listed on his death certificate as intestinal disease of the kidney and urenia. Urenia is linked to renal disease, which sadly claimed the lives of many who worked and were exposed to cotton dust in the mills.

Find out more

Read more about the 1921 Census here: The 1921 Census.

The National Archives has a number of First World War research guides available, which can be found here: First World War Research Guide.

Read our blog about the rehabilitation of Frist World War Servicemen here: Rehabilitation of disabled First World War Servicemen in the 1920s.

What is 20 People of the 20s?

20 People of the 20s is a project where staff members at The National Archives have researched a story of someone from the 1920s. From family members and First World War service personnel, to famous performers and politicians, we hope these stories will encourage you to explore the breadth of experience in 1920s Britain. 20 People of the 20s is part of 20sPeople – our season to mark the release of the 1921 Census, connecting the 1920s and the 2020s. Find out more here.