20 People of the 20s is part of 20sPeople – our season to mark the release of the 1921 Census, connecting the 1920s and the 2020s. This story was researched by Roger, Principal Records Specialist at The National Archives.

20 People of the 20s is part of 20sPeople – our season to mark the release of the 1921 Census, connecting the 1920s and the 2020s. This story was researched by Roger, Principal Records Specialist at The National Archives.

The woman who lost her nationality

An illustration of Hilda Toyokawa, created from a photograph. By Sophie Glover.

Hilda Emily was born in 1892 in Thorpe, Norfolk, to Samuel and Henrietta Futter. In the 1901 Census she is listed as living in Blofield, the youngest of three children, her father and brother both occupied as gardeners. By 1911, she is aged 18 and a housemaid at Garretts Hall, Banstead, Surrey.

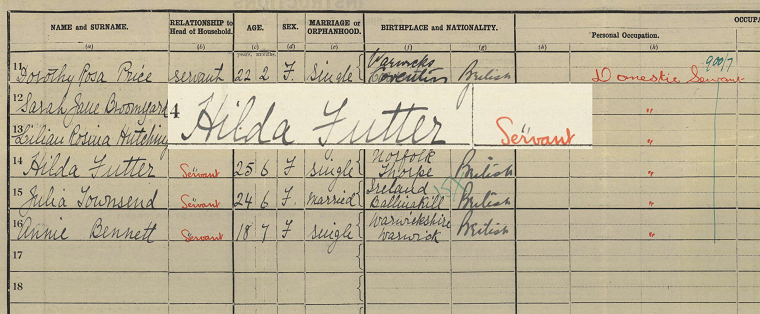

At the time of the 1921 Census, Hilda is listed as a servant at The Castle, Warwick – presumably Warwick Castle. However, only six months after the 1921 Census was taken, both Hilda’s name and nationality has changed. She married Chokichi Toyokawa, a Japanese national, in 1922 – becoming Hilda Emily Toyokawa, and a Japanese national herself in the process. Under the 1914 British Nationality and Status of Aliens Act, Hilda immediately lost her British nationality upon marrying Chokichi.

Hilda Toyokawa’s 1921 Census record. Her relationship to the head of the household is listed as ‘servant’.

The rules at this time only applied to British women – not men – marrying alien or foreign subjects. The 1914 British Nationality and Status of Aliens Act did allow women to apply for naturalisation to reclaim their status as a British national, rather than being named an alien. That said, the Act made it clear that, while there was likely to be no barrier in most cases of re-admission, it was not automatic, and widows and divorced women whose husbands had been foreign nationals still had to apply for re-admission to British national status.

Men did not lose their British nationality on marriage because of the dated legal notions about women in marriage.

The old legal notion described a single woman as a ‘femme sole’ (however a young woman would be under her father’s control) and a married woman a femme covert, i.e., under the control of her husband and legally one legal entity with her husband, thus having no separate identity. Oliver Twist rather encapsulates this idea: Mr Bumble is told he is the guiltier of him and his wife because the law supposes his wife acts under his direction. He responds by saying, “the law’s an ass and the law is a bachelor and its eye should be opened by experience!” By the 20th century, married women did have a legal entity, but still needed their husband’s permission to do certain things.

Women’s activism in the interwar period focused on a number of issues important to women’s lives: equal pay, legislation for unmarried mothers, and a women’s nationality upon marriage. Throughout the early 20th century, various women’s rights organisations sought to address the lack of international laws recognising married women’s rights of national citizenship. These organisations sought to restore the rights women previously had to recognise the independent nationality of married women. They saw the early 20th century position on women and nationality as a step backwards that removed women’s agency, saying it ‘is to continue to treat a married woman as a chattel and not as a person in her own right.’ After the winning of the vote on equal terms, it was issues like this that were key to women’s lives in advocating for a more equal future.

The British Nationality and Status of Aliens Act 1933 did indeed change the law so that women did not lose their British Nationality upon marriage to a foreign subject.

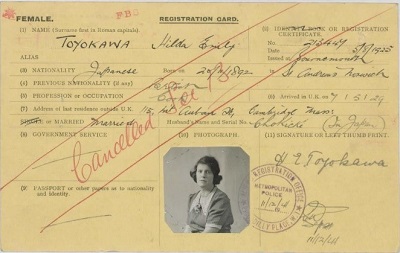

Hilda Toyokawa’s registration card, recording her status after her return to the UK. The card was cancelled in 1943 when she regained her British nationality.

Hilda and Chokichi had two daughters, born in 1922 and 1930. Both Hilda and Chokichi moved to the United States in the 1920s, before Hilda returned to the UK alone in 1929; her occupation is recorded as a housewife on the incoming passenger list. The last entry found for Chokichi places him on a passenger list travelling from Philadelphia to Los Angeles, his occupation recorded as a cook. In the US Archives There is an entry in the US Archives relating to the internment of somebody with the name Toyokawa in 1942, following the UK and US governments’ declaration of war on Japan after the bombing of Pearl Harbour on 8 December 1941.

At some point, Hilda reapplied for British nationality. This is granted, and a certificate of naturalisation issued on 2 March 1943. The background papers pertaining to the application were not selected for permanent preservation, so unfortunately the full story is unavailable. A duplicate copy of her naturalisation is available; however, this doesn’t state that her husband is deceased, so it is assumed he was still in the United States.

The last entry available for Hilda is an entry of her death on 28 August 1960 in Thorpe, Norfolk, the same town she was born in, 68 years earlier. Her name upon death was still recorded as Hilda Emily Toyokawa.

Find out more

Read our guide to researching naturalisation records here: Naturalisation, registration and British citizenship research guide

Curious about our exhibition, ‘The 1920s: Beyond the Roar’? Read our reasons to visit here: Five reasons to visit our 1920s exhibition

What is 20 People of the 20s?

20 People of the 20s is a project where staff members at The National Archives have researched a story of someone from the 1920s. From family members and First World War service personnel, to famous performers and politicians, we hope these stories will encourage you to explore the breadth of experience in 1920s Britain. 20 People of the 20s is part of 20sPeople – our season to mark the release of the 1921 Census, connecting the 1920s and the 2020s. Find out more here.