This story is one of the winning stories in the 20sStreets competition. The competition invited entrants to research and share stories of the 1920s, searching for the most fascinating local history stories covered by the 1921 Census of England and Wales. There were six winning stories and twelve runners-up entries.

Khalid Sheldrake: The East Dulwich man who would be King

By Sharon O’Connor, winner (one of five) in the Individual category

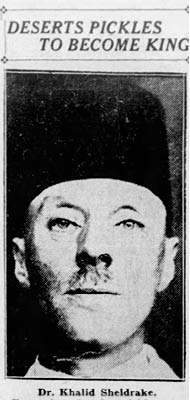

Pictured in the Star Tribune, May 14 1934. Image source: Paul French

Bertie Sheldrake was a South London pickle manufacturer who converted to Islam and became king of a far-flung Islamic republic before returning to London and settling back into obscurity.

Bertie William Sheldrake was born in 1888, the grandson of Gosling Mullander Sheldrake who had started a pickle business in Walworth where Bertie’s father also worked. He was brought up ‘in strict conformity’ to the Church of England but reading free-thinkers like Charles Bradlaugh gradually brought him to Islam, before he had ever met a ‘Musselman’ as he called Muslims then. In 1904, aged 16, he was accepted into the Islamic faith by Abdullah Suhrawardy, taking the name Khalid. He was an active Muslim networker from the start, founding the Young England Islamic Society in 1906 aged just 18. His faith caused friction in his family and in 1912 he said that he was ‘at variance with my nearest and dearest’.

Khalid began work in the family pickle business but switched to journalism, writing about Islam and serving as editor of The Minaret. He was a provocative writer: his suggestion that Napoleon had flirted with conversion to Islam caused uproar in both England and France. He began using his family fortune to promote his new faith, helping to launch the journals ‘Britain and India’ and the ‘Muslim News Journal’.

In WW1 he enlisted and although he had served as a territorial before the war he was not sent overseas as converts were not trusted and were carefully watched. His friend and fellow convert Frank Mohammed Crabtree was accused of being ‘morally and politically undesirable’ and ‘an English Muhammadan crank’. In 1917, aged 29, Khalid married the 20-year-old Victoria Gilbert. She converted, took the name Ghazia.

The Sheldrakes raised their family in East Dulwich in the 1920s. They lived in Tarbert Road and in the 1921 Census they lived in Melbourne Grove before moving to nearby Fenwick Road where they lived until the early 1930s. It was here that they became parents and in 1922, when their son Rashid was born, two Muslim clerics visited Mrs Sheldrake in East Dulwich, ‘their turbans provided some interest in the neighbourhood’. They whispered the Muslim call to prayer into the baby’s ear after which the proud father was taken off to dinner at the Afghan embassy. Their other son, Kemal, was born in 1926.

Sheldrake became a leading English Muslim and was often involved in arguments and schisms. He supported the Woking Muslim Mission but broke away to found the Western Islamic Association. He converted part of his house in Fenwick Road into a mosque, calling it Masjid-el-Dulwich. In 1928 he conducted the funeral service of Sayaid Ali, an elephant keeper at London Zoo who had been murdered in his bed by a rival elephant keeper. The service was held at Waterloo station, after which the coffin was taken on the Necropolis Railway to the Muslim section of Brookwood Cemetery.

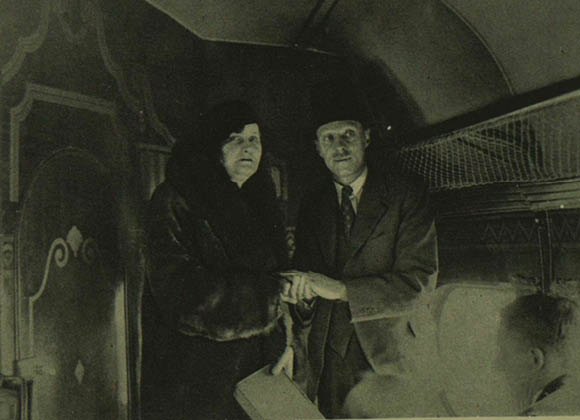

Khalid Sheldrake converting Gladys Palmer to Islam on an aeroplane across the channel. Image source: Paul French

He made quite a name for himself and press speculation in the 1920s and 1930s became the source of many enduring inaccuracies. He was supposed to have been an Irish-French nobleman called Count de la Force though his family came from Suffolk. He was called the ‘Sheik of British Muslims’ though no such title existed. He was supposed to have converted to gain several wives though Ghazia was his only wife. His fame meant he performed high-profile conversions such as that of Gladys Palmer. Gladys was the Quaker daughter of Sir Walter Palmer of the Huntley & Palmer biscuit empire, and the wife of Bertram Brooke, the (Protestant) son of the ‘White Rajah’ of Sarawak. Gladys, who had previously converted to Catholicism and Christian Science, had firm ideas about how her conversion to Islam should go. She wanted it performed ‘on no earthly territory’ so in 1932 she chartered a plane to fly from Croydon to Paris and Khalid performed the ceremony over the Channel with Gladys taking the name Khair ul Nissa. She wore a fur coat and carried a gold copy of the Koran; Khalid wore his customary red fez.

By 1928 there were just three mosques in London: in Woking, Southfields and East Dulwich and Sheldrake expressed disappointment at British Islam’s slow progress for which he blamed sectarianism (division to which he himself contributed). Still, he concluded, there were some positives: ‘We do not conduct our campaigns on the lines of the Mormons’.

Bertram Sheldrake, pictured in Evening Report, March 14 1934. Image source: Paul French

Sheldrake’s fame was growing beyond these shores when, in what is now Xinjiang, the Uygur people were looking for independence from their Chinese masters. In 1933 the Islamic Republic of East Turkestan (known as ETR) was announced, with Kashgar its capital and a population of two million. When China and Russia ignored the fledgling Islamist republic a deputation to Gaynesford Road in Forest Hill, where the Sheldrakes now lived, fell on more fertile ground. The men from Kashgar took tea, admired Mrs Sheldrake’s dahlias and asked: would Khalid become king of the Islamic kingdom and his wife queen? Sheldrake agreed and headed east almost immediately, giving lectures on Islam along the way and telling people of his impending kingship but swearing them to secrecy. By 1934 he had reached Peking where he was closely watched by the Chinese authorities and where he officially accepted the throne and the title His Majesty King Khalid of Islamestan. Ghazia went out to join him, with royal robes sewn by a Sydenham dressmaker and two metal bathtubs made in Croydon.

The British press had a field day: calling him ‘The Pickle King of Tartary’, heading into ‘57 varieties of trouble’ and that he had ‘deserted the ancestral pickle vats of 295 Albany Road’. None of the area’s geopolitical complexities were reported, the story was treated as a jolly jape with many newspapers not even using a photo of Sheldrake but one of a generic Muslim in a fez instead.

In June 1934 the Sheldrakes arrived in their kingdom to find events had overtaken them and the Russians had quashed the fledgling republic. King Khalid and Queen Ghazia headed to Hyderabad where Sheldrake announced, ‘I am not ready to be the pawn of any political game … I am awaiting events before actually proceeding to my kingdom’. But the Sheldrakes never did proceed to their kingdom, instead returning to Forest Hill before later moving to Harrow where Khalid died in 1947 and Ghazia in 1978. There were no obituaries, no press reports. The name Khalid Sheldrake appears to have been forgotten until recently, when scholars have given him his rightful place in the history of 20th century British Islam.

Sources:

Find My Past records including census returns, electoral rolls, newspaper archives, birth, death and marriage certs, church records, military files, education records, 1939 register and of course the 1921 Census. Outside of FMP I used the London Metropolitan Archives, The National Archives, Google Scholar, jstor, abebooks, London Muslim archives, Booth’s poverty maps, Ordnance Survey maps and more!

The rest of the winning and runners-up stories will be published on our 20sStreets portal in the coming weeks.