This story is one of the winning stories in the 20sStreets competition. The competition invited entrants to research and share stories of the 1920s, searching for the most fascinating local history stories covered by the 1921 Census of England and Wales. There were six winning stories and twelve runners-up entries.

This story is one of the winning stories in the 20sStreets competition. The competition invited entrants to research and share stories of the 1920s, searching for the most fascinating local history stories covered by the 1921 Census of England and Wales. There were six winning stories and twelve runners-up entries.

Surviving the 1926 General Strike in a mining community

By Catherine Todd, winner (one of five) in the Individual category

Almost 100 years ago, in circumstances like those experienced today, industrial relations had deteriorated significantly leading to many workers deciding to strike, hoping for higher wages and improved working conditions. The resulting General Strike was not created by recent circumstances but by problems escalating since war time with reduced production and diminishing coal value. It was the most significant dispute of its kind during the twentieth century [1] taking place to ensure that there was enough food on each family’s table and money for children’s school shoes and not for luxuries such as holidays or leisure activity participation.

At the end of the war, many miners returned home discovering that life was tougher than previously. Their families had been through extremely challenging times too as coal prices fell and, after the Armistice, coalmines were returned to private ownership having been government run from March 1917 to the war end.[2] Private ownership resulted in many miners being locked out for several months until they agreed to work for less pay. This is not what they had expected when Lloyd George’s speech in November 1918, proposed that ‘What is our task? To make Britain a fit country for heroes to live in.’[3]

Harry and Edith Todd, from Boldon Colliery, County Durham, were amongst those mining families attempting to earn enough money to keep everyone fed, clothed and warm.

‘Coal owners locked out the miners and demanded they accept the cuts in wages and extended working hours. In South Shields more than 10,000 miners found themselves out of work. Miners across the county found themselves locked out of work with no money coming in.’[4]

In 1921, the Census was delayed due to industrial unrest throughout Great Britain, and when recorded on June 19th, it showed that Harry was unemployed that day.[5] They were living in an upstairs rented flat at 21, Rosebery Terrace, Station Road at the colliery, with their very young children, Tom and Vera.[6]

Boldon Colliery Miner’s Banner – courtesy of the South Tyneside Library Service Local Studies Department

In 1925, mine owners reduced miners pay further whilst increasing working hours. The government provided a nine-month grant to prevent this happening and on 3rd May 1926 the Trade Union Congress called a general strike, with many other unions, particularly the transport unions, showing support by striking alongside the miners. The strike continued until the 12th May but no improvements for the miners were conceded by the owners and they continued to strike until October.[7]

Opinions at the time varied about the strike, the Daily Mail stating:

‘A general strike is not an industrial dispute. It is a revolutionary move which can only succeed by destroying the government and subverting the rights and liberties of the people’[8]

whilst George V was more conciliatory saying

‘Try living on their wages before you judge them.’[9]

Numerous House of Commons debates about the General Strike ensued including one where Joe Batey, MP for Spennymoor in County Durham, warned: –

Ministers did not realise the seriousness of the position in the County of Durham. At the outset I want to say this, that the miners are not a class of people who are content to take starving quietly. They are as fine a set of men as any in the country. They are fair and reasonable, and they are sportsmen and play the game, but they will fight rather than starve, and when they fight it will not be without their womenfolk in Durham. You will find that if the miners have to fight that the womenfolk will stand by their side and will cheer and encourage them to the very last.[10]

Boldon Colliery Pit Buildings – courtesy of the South Tyneside Library Service Local Studies Department

Due to a higher proportion of mining-linked employment in County Durham, the effects of the strike were more widely felt compared to those counties with less dependence on the coal industry. Areas that were similar such as Northumberland and South Wales also suffered comparably from the privations that were caused by the 1926 strike and its consequences.

Conditions at the Boldon Colliery mine were at this time particularly challenging, according to several retired miners, when interviewed by the Shields Gazette in 1982. They had all worked there during the 1920s and 1930s. According to Joe Roberts (retired miner):

‘Some of the [coal] faces were as low as 2ft 6in. Everyone used to wear knee pads. The ventilation was very poor: there was a lot of dust. Men used to work in loin cloths… they couldn’t wear shirts because the sweat used to pour from them.’ [11]

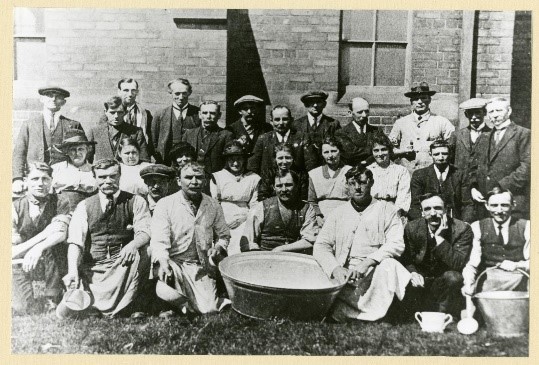

The Boldon Colliery miners were on strike for seventeen months around this time and, in desperation, many dug for coal on the pit heap and frequented a soup kitchen held at the local Wesleyan Chapel. The soup kitchen was run by volunteers using provisions donated by local grocers and butchers who gave vegetables and cheap meat including sheep heads. Things deteriorated so much that several young miners marched to The Workhouse at South Shields to ask to be taken in as they were not able to get any relief.[12]

Boldon Colliery Soup Kitchen Volunteers 1926 – courtesy of the Local History section of South Tyneside Library Service

The thought of The Workhouse for people of that generation, and those preceding it, was one of horror, which indicates their desperation.[13] Young single men occasionally pretended that they had moved away from home by providing authorities a false address. The council believed that they had moved elsewhere making them eligible for relief as they were not living with family.

The strike impacted various institutions including Durham County Council who supplied free school meals for children costing over £250,000 (£12,000,000 equivalent today). Many people needed Poor Law Relief and the South Shields Board of Guardians had an overdraft of £180,000 prior to the strike. The Co-op gave out ten-shilling vouchers which required reimbursement by the Union Lodge when the strike finished, and pawnbrokers were frequently used.[14]

Harry and Edith Todd, recalling the strike decades later, took pride that they were able to survive it without requiring assistance, due to Harry’s allotment and outdoor skills complimented by Edith’s cooking and management skills. Food was grown on the allotment, hens were reared ensuring eggs were available and, on ‘special’ occasions, such as Christmas, chickens were killed for food. All the children were taught early in life how to wring a bird’s neck and pluck feathers. After all the chicken meat was used, the bones were boiled in water to provide stock for the vegetable broth which would be made using vegetables from the allotment and barley added. This provided a substantial meal for several days, especially if they could afford flour to make bread or stotties.

Their son Henry Urwin Todd was born in February 1926 during the strike, and they still managed to cope. Harry taught their elder children Tom, six, and Vera, nine, to snare birds which were taken home and eaten, supplementing anything Harry had managed to grow or forage. Shoes were maintained in a wearable condition as Harry’s brother Loftus, a cobbler, taught his skills to the whole family, whilst many other families’ children were left without shoes. To keep their feet dry, families made makeshift shoes from hessian bags that were previously used to store and transport coal.[15]

Boldon Colliery Miners leaving the colliery post shift circa 1926 – courtesy of the South Tyneside Library Service Local Studies Department

The 1926 strike commenced over a government attempt to reduce miners’ wages. After seventeen months, the men at Boldon Colliery returned to work due to many being near starvation. This was repeated countrywide. Some miners had significant debt or had their homes repossessed and the government had ultimately been successful. On returning to work they were still only paid seven shillings (35p) a day and safety regulations were not improved, despite more than 1,200 miners being killed each year.[16]

Many miners, like Harry, were periodically laid off during the 1930s and part of the pit was closed, meaning ‘people could hardly get a living’. Insecure work meant alternative employment was sought during periods of unemployment. Harry occasionally worked at Boldon Brickworks but occasionally could not find work. Edith would sit with other family members including her youngest son Alan making ‘proggy’ mats which were sold to those family members who were still working.[17] Jean, a relative of Edith, recalled eighty years later how they collected strips of used clothing and other material for Edith, who would then use a frame to stretch a coal hessian bag over. This was used as the mat backing, whilst the woven rags made a colourful front. The mat was returned to the original family member, and Edith would be paid for her work.[18]

The hardships experienced were later emphasised by Harry and Edith’s son, Alan, who recalled that Boldon Colliery folk ate much better and more nutritiously after the Second World War started when rationing began. He also reminisced how family and community spirit provided support for those less fortunate while maintaining an enjoyable life.[19]

All photos courtesy of the Local History section of South Tyneside Library Service

Reference footnotes:

[1] Working Class Movement Library

[2] Hansard Coal Mining (State Control) HC Deb 27 March 1917 vol 92 cc280-95

[3] Shields Gazette ‘Make Britain Fit for Heroes to Live In’ 23 November 1918 South Shields, County Durham p3

[4] Northumberland Archives Blog Peter Connelly ‘The 1921 Coalminers Strike: Part One’ 30th March 2022

[5] National Archives 1921 Census England and Wales Boldon Colliery, County Durham RG15/25095/301/E/556/5/13

[6] Ibid

[7] www.nationalarchives.gov.uk Cabinet Papers Home/The General Strike/Strike Build Up

[8] Daily Mail ‘Effort to end the Great Strike 3rd May 1926 London P1 Col 1-6

[9] Kenneth Rose, King George V (Weidenfeld and Nicolson: London, 1983) p340

[10] Hansard HC Deb.8 February 1926 ‘Coalminers- Durham’ vol 191 cc781- 804

[11] Shields Gazette, ‘Eye on the News’ March 11, 1982, South Shields, County Durham

[12] Tom Bainbridge The Boldons (The History Press: Cheltenham, 1998)

[13] Todd Family Archives Recollections of Edith Davison Todd (nee Urwin)

[14] Shields Gazette, May 26, 1994 South Shields, County Durham

[15] Todd Family Archives Recollections of Alan Todd

[16] Shields Gazette op cit

[17] Todd Family Archives Recollections of Alan Todd

[18] Todd Family Archives Recollections of Jean Henderson

[19] Todd Family Archives Recollections of Alan Todd