Teachers' notes

The majority of the sources in this themed collection have been taken from our Cold War web resource with which many users of the Education Website will be familiar. However, we have upgraded the quality of the images, shown more of the original document in some cases and included additional sources from The National Archives exhibition: Britain’s Cold War revealed: Protect and Survive, April-November 2019.

The purpose of this document collection is to allow students and teachers to develop their own questions and lines of historical enquiry on the Cold War. Students could work with a group of sources or single source on a certain aspect. Teachers may wish to use the collection to develop their own resources or encourage students to ‘curate’ their own ‘exhibition’ of the most significant sources on the topic. Another idea would be to challenge students to use the documents to substantiate or dispute points made in the introduction with this collection. We hope that the documents will offer students a chance to develop their powers of evaluation and analysis and enrich their understanding of this topic.

Alternatively, teachers could use the Cold War website alongside this collection for specific questions or activities connected to these documents.

Students will find more documents in our recommended resources and can also consider film sources as interpretations of these events in relation to the documents by following the links to British Public Information films and British Pathé.

Themes covered in this collection include:

How strong was the wartime alliance, 1941-45?

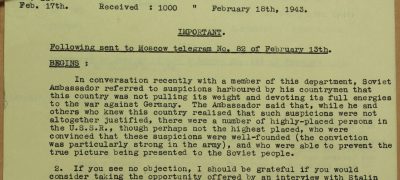

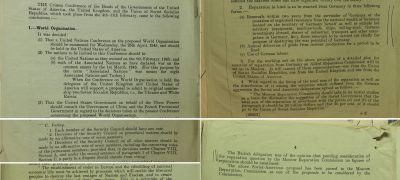

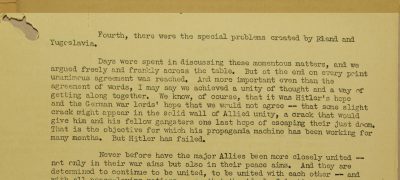

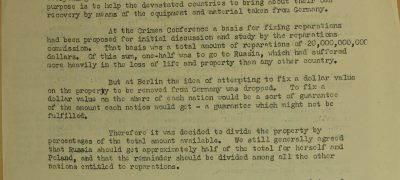

The records provided here give context for a study of the Cold War, with reference to the Yalta and Potsdam Conferences which bridge the period of wartime co-operation and the post war tensions that followed.

Who caused the Cold War?

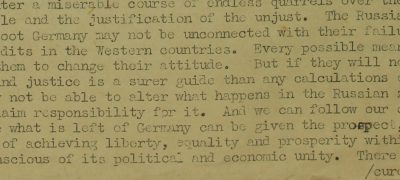

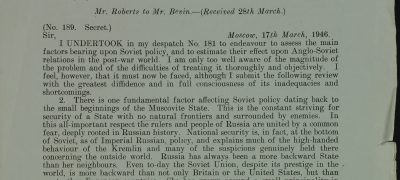

The attitudes and responses of important individuals in the early stages of the Cold War – Stalin, Truman and Churchill are explored through various cabinet discussions and foreign office reports.

How did the Cold War work?

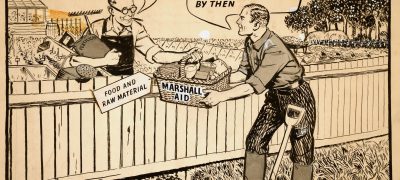

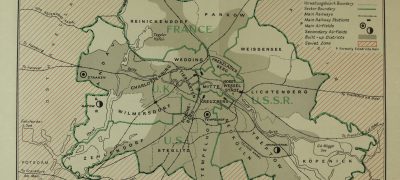

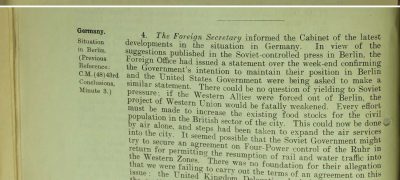

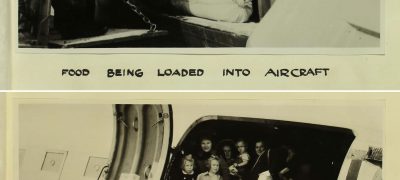

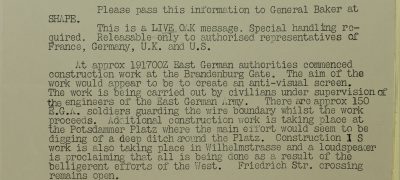

Documents for this theme highlight the nature of the Cold War including the conflict over Berlin in 1948, the blockade and airlift. Other sources reflect the conflict in Korea and Soviet actions in Hungary (1956) and Czechoslovakia (1968) as told through political, military or personal themes.

How close was world nuclear war in the 1950s and 1960s?

Records included in the collection relate to the development of nuclear weapons, British defence policy and the Cuban Missile crisis in 1962.

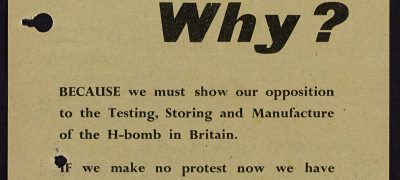

Britain in the nuclear age

For this theme we have included some documents featured in our exhibition called Britain’s Cold War revealed: Protect and Survive which concern civil defence, protests against the bomb at Aldermaston and Greenham Common.

Connections to the Curriculum

These documents can be used to support any of the exam board specifications covering the Cold War, such as:

AQA: GCE History

Unit 2R: The Cold War, c1945-1991

OCR: GCE History

Unit Y113: Britain 1930-1997: British Period Study: Britain’s position in the world 1951-1997 (Enquiry topic: Churchill 1930-1951)

Unit Y223: Non-British Period Study: The Cold War in Europe, 1941-1995

Edexcel: GCE History

Paper 3, Option 37.1: The changing nature of warfare, 1859–1991: perception and reality

Edexcel: GCSE History

Period Study 4: Superpower relations and the Cold War, 1941–91

AQA: GCSE History

BC Conflict and tension between East and West, 1945–1972

Introduction

Who first coined the phrase “Cold War”? The general consensus among historians is that it was the celebrated author and journalist, George Orwell, in his essay ‘You and the Atom Bomb’ published in the Tribune magazine on 19 October 1945 (though one biographer has traced his use of the phrase back to 1943). In the 1945 article Orwell reflected on the repercussions of ‘a state which was at once unconquerable and in a permanent state of “Cold War” with its neighbours’. He envisaged ‘the prospect of two or three monstrous super-states’ dominating the world, and possessing weapons which can kill millions in seconds. Orwell concluded that the atomic bomb was likely ‘to put an end to large-scale wars at the cost of prolonging indefinitely a “peace that is no peace”.

Seeing into the future

Looking back at Orwell’s predictions, he possessed amazing foresight. The Cold War (1945-1991) was a confrontation, both military and ideological, between two superpowers, the capitalist United States and the communist Soviet Union (and their respective allies), made all the more tense by the threat of nuclear war. This highly charged stand-off was a thread running through historic developments such as the iron curtain, the Cuban missile crisis and the construction and dismantling of the Berlin Wall.

Because there was so much at stake – arguably, the very future of civilisation – the superpowers avoided direct confrontation but fought a series of savage proxy wars, in Asia, Africa and Latin America, supporting local factions. Orwell’s “peace that is no peace” prediction was borne out.

Revelations

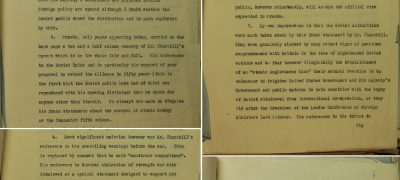

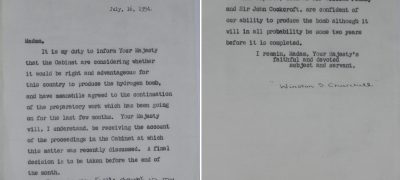

Contemplating the Cold War from today’s perspective, one aspect cannot be predicted – the surprises that can emerge from documents you haven’t seen before. Many narratives are available for the Cold War: it is the subject of many books, documentaries and films. However, this package of documents from The National Archives shows us that archives still have the capacity to surprise us about this period in history. There are many instances of this. For example, it is well-known that Churchill’s famous quotation “from Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic, an iron curtain has descended across the Continent” was part of a speech given in Fulton, Missouri, USA, on 5 March 1946. But did you know that he used the phrase ‘iron curtain’ almost a year earlier, in a personal telegram to President Truman on 12 May 1945? This is a heartfelt message in which Churchill expresses his ‘deep anxiety’ about Russian intentions in Eastern Europe.

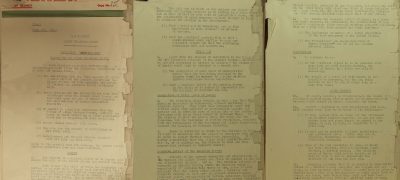

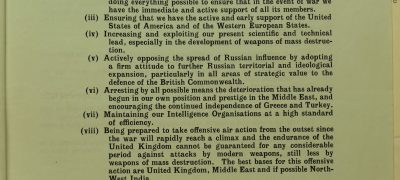

Another surprise is a report by the Joint Planning Staff which puts forward a plan, (little known today) entitled ‘Operation Unthinkable’, advocating an attack on Soviet Forces in order to push them out of East Germany and Poland in July 1945. This document has real ‘shock value’: ‘If they [the Russians] want total war, they are in a position to have it’. The strident language of this document is striking: the intention was ‘to impose on Russia the will of the United States and the British Empire’. However, it is acknowledged that ‘to win would take us a very long time’.

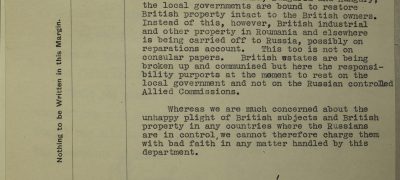

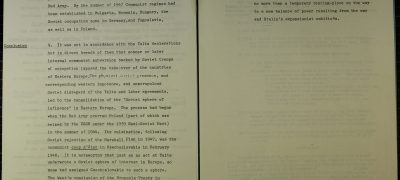

Dramatic language is also a feature of a report called ‘The Threat to Western Civilisation’ from the Foreign Secretary to the British Cabinet in March 1948. This refers to the possibilities of the Soviet Union establishing a ‘world dictatorship’ or the ‘collapse of organised society over great stretches of the globe’. The writing style is so powerful, the words leap from the page. Yet another example of vivid writing can be seen in a Foreign Office telegram reporting back to London about the uprising in Hungary on 25 October 1956: ‘the populace are terrified of massive reprisals’.

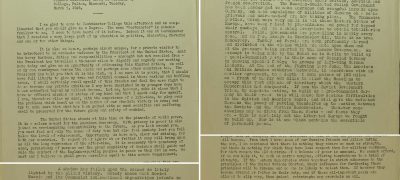

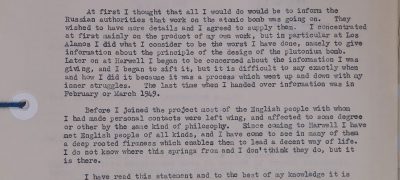

In some cases, document content is not dramatic in itself but is, none the less, surprising. A great example of this is the last paragraph of Atomic Spy Klaus Fuch’s confession on 27 January 1950, when he suddenly begins to ‘wax lyrical’ about his admiration for English people: ‘since coming to Harwell I have met English people of all kinds, and I have come to see in many of them a deep rooted firmness which enables them to lead a decent way of life. I do not know where this springs from and I don’t think they do, but it is there’. This incongruous piece of reflectiveness at the end of a confession statement shows how Fuchs was somewhat detached from reality at the time he made it – the does not seem to realise the import of what he had just confessed to, the giving of vital atomic secrets to the Soviet Union.

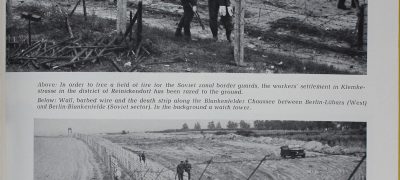

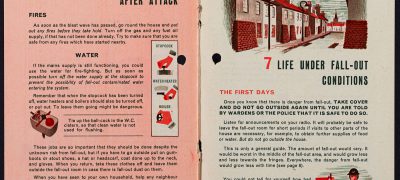

As well as the textual documents, visual sources can also tell a powerful story. Grainy black and white photographs of the early days of the construction of the Berlin Wall make us reflect on the predicament of Berliners, looking on at the partially constructed wall, the barbed wire, the turrets, and the ‘death strip’. For another striking example of visual material, see the illustrations in the leaflet advising householders on protection against nuclear attack (1963), which are strangely cosy, hinting at elements of normality even during fall-out conditions.

Value of archives

The National Archives is the nation’s memory – we preserve the integrity of the public records, stretching back some 1,000 years. George Orwell truly understood the value of authoritative records: Winston Smith, the anti-hero of Orwell’s 1984, worked in the ‘Ministry of Truth’, falsifying back-numbers of The Times so that the information contained in them corresponded with the current pronouncements of Big Brother’s regime. The corollary of this imagined scenario, of course, is that archives you can trust are essential for a true understanding of the past.

Mark Dunton

Principal Records Specialist

The National Archives

External links

Pathe Archive film collections covering various conflicts during the Cold War – https://www.britishpathe.com/pages/collections

Back to top