Download documents and transcripts

Teachers' notes

This collection of original documents can be used to support GCSE units on modern British immigration for AQA History: Britain: Migration, empires, and the people: c790 to the present day; Edexcel, Migrants in Britain c800-present; OCR, Migrants to Britain c1250 to present (Schools History Project) and for ‘depth studies’ on ‘Modern Britain’ at A Level for AQA and Edexcel.

Some of sources could be selected by teachers to support history lessons for the Key stage 3 unit: ‘Challenges for Britain, Europe, and the wider world 1901 to the present day: social, cultural, and technological change in post-war British society; Britain’s place in the world since 1945’.

This collection of original documents is particularly useful for knowledge selection on modern British migration. Teachers can use it with students to develop their own historical enquiries as well as to prepare and practice source-based exam questions. The collection includes a wide range of source types to encourage students to think more broadly when exploring attitudes towards migration and its impact. Teachers have the flexibility to download all documents and transcripts to create their own resources.

It is important to note that many documents cover sensitive subjects. Some include language and concepts that are entirely unacceptable and inappropriate today. We suggest that teachers look at the material carefully before introducing to students. It would be helpful to discuss the language and ideas contained in a source beforehand. Teachers may wish to break the documents into smaller extracts if they appear too long or create additional simplified transcripts.

Please note that the government film on the Race Relations Act 1968 is a public record created in 1969. It was also released in Hindi and Urdu. It has been preserved and presented by the BFI National Archive on behalf of The National Archives. Courtesy of the BFI National Archive. It includes language which may be considered offensive. However, we think it important to show the film as accurate representation of the record to help us understand the past.

With each document we have provided a ‘brief descriptor’ on the web page to signal the content; a document caption, and 3-4 suggested prompt questions. We hope this will allow students to work independently if wished on any document, or within small class discussion groups, or to assist teachers in the development of their own questions. Also included in these notes is a suggested starter activity. The aim is to familiarise learners with the types of sources contained in the collection. We hope too that exposure to original source material may also foster further document research.

Types of records

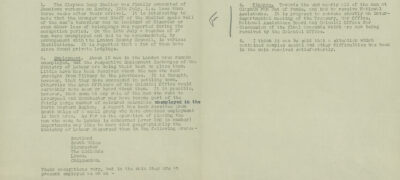

The collection allows the students to explore different types of government records including: the Home Office (HO), the Colonial Office (CO), the Foreign Office (FO), Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO), the Ministry of Labour (LAB), Board of Trade (BT), Assistance Board (AST), Admiralty (ADM) and the Ministry of Information (INF). Here is a short video introduction to records at The National Archives.

It is worth discussing with students the functions of these various departments and there is more detail in The National Archives’ research guides on individual record series, for example: the Foreign Office and its successor, the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, or the Home Office.

Looking at different types of sources

Starter Activity: 15 minutes

Students look at the document collection.

Find an example of each source in the table below. Fill in the reference of the source & answer the two questions in the table. Discuss your findings if possible.

| Source type | · Which government department does the source come from?

· How does this help to understand more about the source? |

| Ship’s passenger list

Ref: |

|

| Local Newspaper

Ref: |

|

| Government Report

Ref: |

|

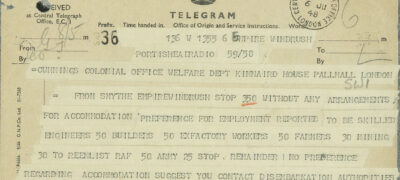

| Telegram

Ref: |

|

| Handwritten letter

Ref: |

|

| A typed official letter

Ref: |

|

| Memorandum

Ref: |

|

| Photograph

Ref: |

|

| Registration of British Nationality form

Ref: |

|

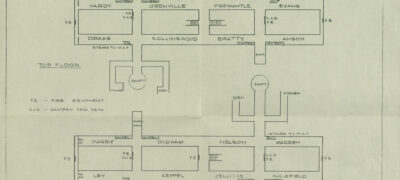

| Diagram

Ref: |

|

| Statistical information

Ref: |

|

| Copy of a speech

Ref: |

Source questions

Once students get to grips with the type of source, they can work out what is being said and how is it being said. Encourage them to ‘look behind the source’. Where has the record come from and why has it been created? Does it offer a national or local perspective? What is the difference between a government report and a local newspaper? What is the value of oral testimony? What type of sources help with specific investigations?

Encourage students to consider both the ‘witting’ and ‘unwitting’ testimony a source may reveal. Part of this evaluation is to consider if there are any gaps in the evidence or issues of accuracy in authorship. Why would we trust/not trust this source? What other sources might be needed to provide additional information/context? Does the document support other knowledge that you already have for a certain line of enquiry? Use the document prompt questions to promote discussion of the content.

Finally, some photographs are included in the collection. Students should always consider: why has the photograph been taken? Is it posed, is it an official press photograph, or is it a snapshot? Remember too that a photograph can be selective in choice of subject – or could it have been cropped? Is there an original caption linked to the photograph? Original captions add meaning to a photograph and add a particular message – we cannot necessarily take them on face value.

The purpose of the following questions is to analyse, evaluate and understand the documents to develop interpretations and draw conclusions. Teachers may wish to print out them for discussion prior looking at the collection.

- What is the date of the source?

- Who wrote/created it?

- Do you know anything about the author?

- What type of source is it? (Letter, report, newspaper, telegram, diagram, photograph, memorandum, statistical data)

- What is the source saying/showing?

- Check the meaning of any words you are unsure about.

- How useful is this information, does it support what you know already?

- What can you infer (information which is not directly stated)?

- What type of enquiry would be this record be useful for?

- Does the document show the writer’s opinions/values?

- Are there any clues about the intended audience for the document?

- Why was the document created?

- Does it have any limitations or gaps?

- Does it link to other sources in this group?

- Does it share the same ideas, attitudes, and arguments?

- How would you explain any differences between these documents?

Suggested enquiry questions using documents in this collection

Ensure that students refer to specific named documents as part of any enquiry. Break the class up into groups and get students to feedback and/or annotate at a white board which sources could be relevant to any of these suggested enquiries:

- For what reasons did people choose to migrate from British colonies to Britain after the Second World War?

- How and why did the British government prepare for the arrivals on the Empire Windrush?

- Where did the first Empire Windrush arrivals find work and settle?

- Why and what arrangements were made for the reception of V.W.s [European Voluntary Workers] and ex-Polish servicemen?

- What do the documents reveal about attitudes towards migrants and the experience of migrants living in Britain in the 1950s and 1960s?

- How did government legislation in Britain impact on migrants coming to Britain in the 1960s and 1970s?

- Select THREE sources that you have found most interesting/shocking/surprising and compare with a partner/discuss in class.

- Use the documents here, the Background, and your own research to create a timeline entitled: ‘Migration in Modern Britain from 1905 (Aliens Act) to the present’.

- Listen to the oral testimonies provided in the external links below from the British Library and London Docklands Museum. How to these deepen our understanding of the documents concerning experience of the Empire Windrush arrivals and later migrants? Discuss in class.

- Use appropriate documents from this collection to provide a national context for your own GCSE historic environment local migrant case study from 1940s-1960s.

Connections to curriculum

Key stage 4

AQA GCSE History: Britain: Migration, empires, and the people: c790 to the present day

Edexcel GCSE History: Edexcel, Migrants in Britain c800-present

OCR GCSE History: OCR, Migrants to Britain c1250 to present (Schools History Project

Key stage 5

AQA GCE History: The Making of Modern Britain, 1951–2007: Attitudes to immigration; racial violence 1951-1964 & Issues of immigration and race 1964-1970.

Edexcel GCE History British Political History, 1945- 90: Consensus and Conflict

Key stage 3

Challenges for Britain, Europe, and the wider world 1901 to the present day: social, cultural, and technological change in post-war British society; Britain’s place in the world since 1945. 1964-1974 issues of immigration and race

Introduction

Commonwealth migration to Britain

Migration from the Caribbean to Britain, symbolised by the arrival of the Empire Windrush, hides the fact that there had already been a long tradition of men and women emigrating from islands such as Jamaica to work in Central and South America and the United States. The Caribbean economy, heavily reliant on the export of agricultural products, was an economy where labour was cheap and unemployment rates high, so seeking seasonal work, particularly in the US, was normal. After the Second World War, there was a dramatic reduction in the requirement for Caribbean labour in the US, and this was an important push factor for the arrival of Caribbean men and women to Britain from the late 1940s and early 1950s. In addition, there was more familiarity with Britain, as during the Second World War people from the Caribbean had come to serve in the war. In the wake of the arrival of the Empire Windrush, consideration was given by British officials to restrict further arrivals; however, there was resistance, most notably from the Governor of Jamaica, who could see the tough economic conditions people were operating under and acknowledged that people were British subjects and had only recently contributed to the war effort.

British cities needed rebuilding after the devastation of five years of bombing. Britain also had to recruit a huge number of workers to support the newly founded Welfare State and to rebuild its infrastructure.

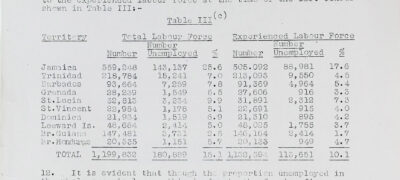

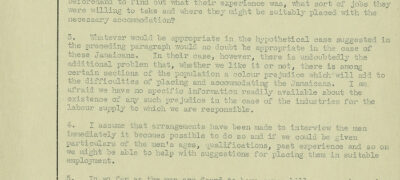

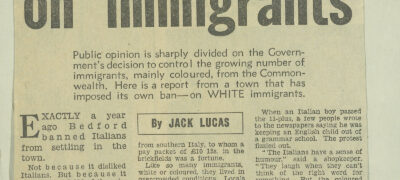

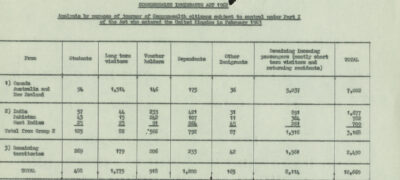

There was a significant demand for labour which came not only from the Caribbean but also from mainland Europe, Ireland, India, and Pakistan. However, it was opposition to Commonwealth and empire immigration that stood out, with a reluctance for example to accept skilled Caribbean labour. While wanting to allow entry to white people from the old Commonwealth, the government did not want to appear racist in any plans to restrict immigration from elsewhere in the empire and Commonwealth as governments of the newly emerging black Commonwealth took offence at moves to restrict movement to Britain from their respective countries while not applying the same rules to those from the white Commonwealth.

European Volunteer Workers Scheme and Polish resettlement

There was also the question of European migration. Polish troops who fought alongside the western allies chose not to return to Poland. In 1946, the British Foreign secretary announced that the Polish Resettlement Corps was to be formed as a body of the British Army whereby any Pole who served under the British would be discharged from the Polish Army and could enlist as a British soldier until demobilization. Wives and dependents were brought to Britain to join them. The Polish Resettlement Bill was drawn up in 1946 and the Act was passed in 1947. It was the first ever mass immigration legislation passed by Parliament in Britain and allowed over 200,000 Poles to remain in the United Kingdom.

The Polish Resettlement Corps was disbanded in 1949. During its short-lived existence, it brought about the reunion of families and integration into British society for displaced Poles. It was these Poles who established the Polish communities throughout the United Kingdom.

Over 84,000 or so European Voluntary Workers (EVW) arrived in Britain from 1947-1949. The Displaced Persons (DPs) who were brought to England as EVW to supplement Britain’s workforce were East Europeans who were taken as forced labour by the Germans, being held after the war in the military zones in Germany.

Arrival of the Empire Windrush and beyond

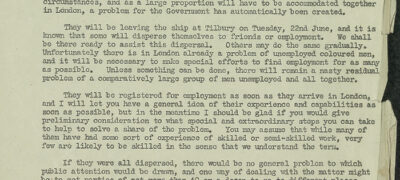

Before the much-publicised Empire Windrush docked at Tilbury Harbour in June 1948, earlier ships arrived at UK ports carrying West Indian labourers . The Ormonde, for example, docked at Liverpool in March 1947 with 108 migrant workers from Bermuda, Trinidad and Tobago, and Jamaica. At the end of that year, the Almanzora arrived at Southampton with a similar number of mainly ex-service men from the West Indies who had fought alongside Britain and her allies.

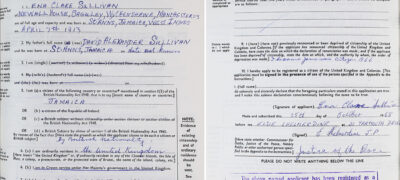

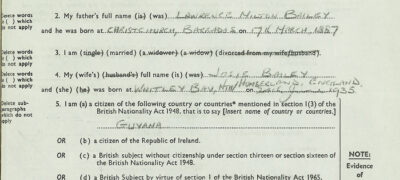

Many migrants travelled alone, leaving behind their families while they settled in. There was an acute shortage of housing, particularly in big cities, to accommodate the growing number of migrants and many endured racist abuse and were denied access to hostels. The problem was so severe in London that many were housed in a deep underground shelter at Clapham Common. The British Nationality Act 1948, which came into force on 1 January 1949, made it much easier for Commonwealth migrants to settle in Britain as it created the opportunity for all to register their British Nationality.

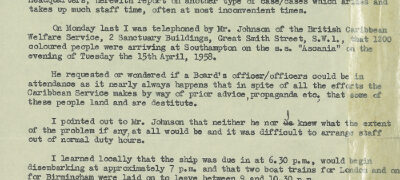

By June 1948, a variety of Government Departments including the Home Office, the Ministry of Labour, the Assistance Board, and the Housing and Local Government Board were becoming more co-ordinated in preparing for future influxes of Caribbean migration across the United Kingdom. The 1950s would see the arrival of tens of thousands of workers and their families as Britain continued its policy to nationalise key industries, such as transport and energy, and with it demand more labour.

Nearly 70 years after the arrival of the Windrush, it emerged in 2017 that hundreds of Windrush generation migrants had been wrongly detained, deported and denied legal rights, despite having lived in the UK since before 1973. In March 2020, Home Secretary Priti Patel apologised for the scandal and the harm inflicted upon families.

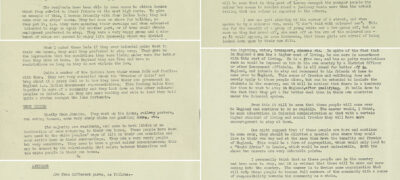

Experience of the first arrivals in the 1950s and 1960s

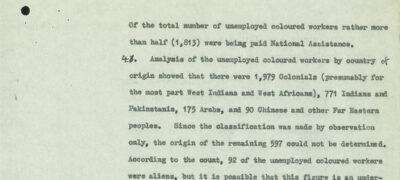

The Empire Windrush (BT 26/1237) as well as the Ormonde, Almanzora, and many other ships’ passenger lists reveal a diverse range of skills and professions amongst the migrants, including accountants, chemists, carpenters, and more. However, as a result of the colour bar in Britain, many could only find employment in the least desirable areas of the economy, in work that was typically semi- and unskilled, with low wages and poor conditions. Indeed, a study by the sociologist Ruth Glass carried out between 1958-91 showed that 55% of Caribbean migrants experienced job downgrading after their arrival.

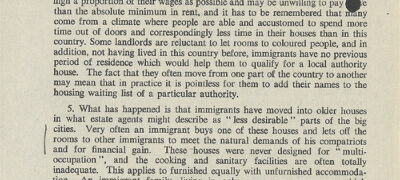

In housing, many of the West Indians’ initial stays in the air raid shelters underneath Clapham South underground station (HO 205/253) only served to delay their confrontation with landlords reluctant to let rooms to Black people, with the now infamous ‘no blacks, no dogs, no Irish’ signs displayed in lodging house windows.

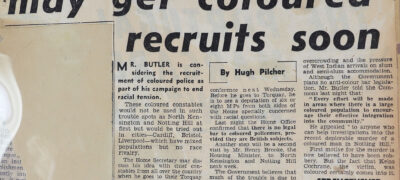

This hostility would grow throughout the 1950s, culminating in the Nottingham and then Notting Hill (West London) riots of 1958, which largely consisted of gangs of Teddy boys attacking the new arrivals. The following year, Kelso Cochrane, a carpenter from Antigua, was brutally stabbed to death in West London. These events would lead to increased calls for immigration control, resulting in the 1962 Commonwealth Immigrants Act, leading many to argue that the migrants were being blamed for the prejudice directed towards them.

Racism was, however, always met with resistance. The Caribbeans, for instance, downed tools and walked away, and petitioned and organised against discriminatory practices in the workplace (even where unions weren’t supportive). They developed ‘pardner’ or ‘sou-sou’ schemes to raise money for down payments on homes (as banks would frequently refuse to lend to Black people), and mobilised against racist attacks in the streets. Claudia Jones emerged as a key activist in this period, founding the West Indian Gazette Newspaper and, following the Nottingham and Notting Hill riots in 1958, organised the UK’s first Caribbean-themed carnival in St Pancras Town Hall, London.

1 Glass, Ruth (1960) Newcomers: The West Indians in London Harvard University Press, p.31, cited in, Hiro, Dilip (1992) Black British, White British: A History of Race relations in Britain Paladin, p26.

External links

External links

- Runnymede Trust: Our Migration story website: Stories from 1900 to 2000

- Watch short film portraits from Londoners of Caribbean heritage: British Library

- Articles and historical sources from the British Library on Windrush

- Museum of London Docklands oral history collection called ‘Listening to the Windrush generation’

- More photographs and film about the Empire Windrush from Royal Museums Greenwich

- Articles from the Windrush Foundation

- Workshops at the Black Cultural Archives including Windrush

- Explore collections at the Migration Museum

- Students could consider British Pathé film sources as interpretations of the migration post 1945 in relation to this learning resource.

Research guides

- The National Archives website: Immigration and immigrants

- The National Archives Education website: Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic histories