How to look for records of... Civil court cases: Court of Common Pleas

How can I view the records covered in this guide?

How many are online?

- None

1. Why use this guide?

This guide will help you navigate records of the Court of Common Pleas, 1194-1874.

If you are researching a person between the 12th and 19th centuries these records can be very valuable. These and other common law (law developed by judges from precedent in previous trials, as opposed to laws made by statute) records are the largest source of dated references to individuals until the start of parish registers.

These records are a rich source of information on:

- the development of common law and the legal process

- the judges, court officials, and local officials

- the lives of the many individual litigants, particularly in relation to property and debt disputes

These records are predominantly sheets of parchment joined together at the top to form large rectangular rolls, and can be difficult to locate and consult. Records before 1733 are in Latin.

Courts in session at the north end of Westminster Hall. The British Museum, early 17th Century (Creative Commons)

2. What was the Court of Common Pleas?

The Court of Common Pleas was a common law court hearing actions between private individuals against each other.

The court had its origins in the 12th century and sat at Westminster Hall (but also at Shrewsbury in Edward I’s Welsh wars, and on many occasions at York during the Scottish wars of Edward I, Edward II, and Edward III). The court’s jurisdiction was originally unlimited, except that it could not hear actions from the palatinates and the more highly privileged liberties and boroughs. From the reign of Edward I, the court became increasingly limited to civil litigation at common law between subjects. Eventually this limitation became rigid and the court came to be called the Court of Common Pleas.

There was an on-going conflict between the Kings Bench and Common Pleas courts over their respective shares of civil litigation. This was only settled after 1660.

The court was abolished by the Supreme Court of Judicature Act of 1873, and Common Pleas became a division of the High Court of Justice. In 1880, by an Order in Council, the Common Pleas Division was amalgamated with the Queen’s Bench Division of the High Court of Justice.

3. Jurisdiction

The court came to include three main sorts of jurisdiction.

The first and most important was its common law jurisdiction over civil litigation, cases brought between private individuals against each other and begun by original writ from the Chancery. The court had exclusive jurisdiction in real actions, those involving rights of ownership and possession in land; in the older personal actions of debt, detinue, account, and covenant; and finally, in the mixed actions, both personal and real, such as ejectment.

Jurisdiction was shared with the King’s Bench in maintenance, conspiracy, other breaches of statute, trespass, trespass on the case, and their derivatives.

The court also held two sorts of jurisdiction by privilege. Firstly, justices as conservators of the peace could try even criminal cases when the cause of action arose within the court or among its records. Secondly, they had jurisdiction by privilege in suits brought by or against officers of ministers of the court.

4. An overview of the records

The court began recording its proceedings in plea rolls and filing its writs from its foundation at the end of the 12th century. As its business increased new series of files were created for new kinds of writs and instruments, especially in mid-late 16th century.

The different offices of the court developed from the thirteenth century onwards. In 1838, most of these offices were abolished and the duties transferred to five masters, to whom the records of the abolished offices were transferred.

The arrangement of Common Pleas records in our catalogue reflect these different functions. The links below are to divisions in our catalogue corresponding to different aspects of the court’s work. Each division is further divided into series, representing types of document. Individual documents can be found by browsing or date searching within the series.

4.1 Records relating to the Conveyancing of Land and Property Title (1195-1876)

One of the main functions of the court was to provide the means of conveying real property through court procedures involving collusive litigation. The principal means involved were the levying of final concords and the enrolment of common recoveries. This division contains all those surviving documents whose functions were directly related to the conveyancing of property or title before 1833.

Browse the division Records relating to the Conveyancing of Land and Property Title

See our guides to conveyances by feet of fines and to enrolment and registration of title.

4.2 Records relating to Pleas (c 1194-1880)

Records of pleas held in the Court of Common Pleas relate to both legal process, and to the recording of court proceedings.

Browse the division Records relating to Pleas

See sections 5 and 6 below.

4.3 Records relating to Outlawry (c 1500-1870)

Records of the Court of Common Pleas, extracted from the plea rolls, relating to outlawry as process against defendants who failed to appear in court.

Browse the division Records relating to Outlawry

See our guide to outlaws and outlawry.

4.4 Administrative records of officials of the Court of Common Pleas (1654-1875)

Administrative records of officers of the Court of Common Pleas are primarily records of appointment (grants of office or admission to offices), articles of clerkship, and attorneys’ admission to practice in the court.

Browse the division Administrative records of officials of the Court of Common Pleas

Enrolments of the appointment of justices of the court occur intermittently on the patent rolls from Henry III, see our guide to Royal grants in letters patent and charters from 1199.

5. Plea rolls

Plea rolls are both the most informative records of a case in the Court of Common Pleas and the easiest means of access to cases.

These records survive from the beginning of the reign of Edward I until the court’s abolition in the nineteenth century. The main series of plea rolls is CP 40.

Each roll covers a term and is made up from individual rotuli which carry a formulaic record of pleading and process in the court. They do not record what was actually said by the serjeants at law, who had a monopoly of pleading in the court by 1300, and the judges.

‘Year books’, which exist from about 1270 onwards and were principally concerned with reporting cases in the Common Pleas, record reports for the medieval period. Printed versions of some of these ‘Year book’ are available in the Map and Large Document Reading Room at The National Archives. A searchable database of the printed ‘Year Books’ is available online. Manuscript and printed law reports take over reporting for early modern cases.

Each roll is, as in the case of other series of plea rolls, made up of a large number of individual rotuli or rolls, single sheets of parchment normally used on both sides and filed together at the head to make up the whole unit.

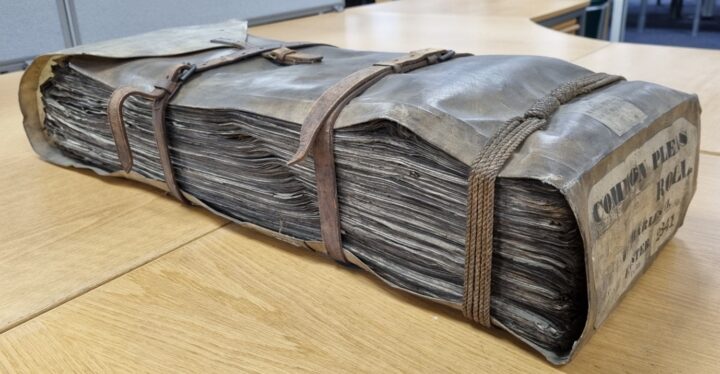

Plea Roll, Easter term 1654, CP 40/2641

From 1290 each rotulus was numbered at the foot, and from 1305 each one also carries the surname of the clerk who compiled it and handed it in. From 1327 until the end of the court’s life in 1875 there is a single, almost unbroken series of rolls made for the chief justice of the court and bearing his name.

The plea rolls reached their greatest size in the early 17th century, and thereafter declined, partly because of a decline in business but also because the attorneys who by then drew them up often failed to hand them in for filing.

Essoin rolls

The plea rolls do not include essoins (excuses for not appearing in a law court) but do contain separate sections for warrants of attorney and for the enrolment of charters and other deeds. Essoin Rolls are in CP 21.

Rex Rolls

From 1272 to 1327 there is an additional but incomplete series of rolls headed ‘Rex’ (CP 23) kept by the keeper of the writs and rolls. The reason for their compilation is not known but they appear to transcripts of plea rolls. During the first 19 years of Edward I there are a few rolls, including the same material, made for junior or puisne justices of the court, but there are no more thereafter.

Recovery rolls

From 1583 pleas of land were removed into the recovery rolls (CP 43), and what we now call ‘plea’ rolls came generally to be known as ‘common rolls’. The two series of rolls were eventually reunited in 1838 (CP 40/3984), and a few enclosure awards were enrolled in the plea rolls during the following 15 years.

Digital images of some of the records in this series are available through the Anglo-American Legal Tradition website. Please note that The National Archives is not responsible for this website or its content.

6. Finding plea rolls

6.1 Searching

To find the plea roll for a particular case, you will need to know in which year and law term (e.g. Hilary, Easter, Trinity, or Michaelmas) the case occurred, as catalogue descriptions for plea rolls in CP 40 only include this information.

For example, to find the plea roll for a case that occurred in Michaelmas term 1598, you would need to search CP 40 for “Michaelmas” in 1598. Instead of the calendar year, you can also search by regnal year, so a search for “Michaelmas” and “40/41 Eliz I” will also identify the correct plea roll, CP 40/1615.

6.2 Using other records to find plea rolls

There are in general no indexes to the plea rolls, although there are a number of contemporary finding aids that can be used to help a search. These include the prothonotaries’ docket rolls in CP 60, 1509-1859. The docket rolls were probably compiled for the collection of fees, but they do give direct references to the rotuli and so can be a useful means of reference. Early docket rolls cover a number of years, by the nineteenth century they are annual.

From the middle of the sixteenth century the termly entries give the county, the names of the attorney, plaintiff and defendant and the kind of entry made. Until 1770 there are three separate series of docket rolls: one for each of the three prothonotaries. In order to check all the entries for a particular term, you have to use all three rolls. There are gaps in each of the three series. No docket rolls survive for the period 1770-1790. From 1791 onwards there is a single series, which ends in 1859. The catalogue descriptions for plea rolls in CP 40 include the corresponding docket rolls for that term.

Between 1859 and 1874, similar information is contained in the Entry Books of Judgments in CP 64.

An entry book of judgments for pleas recorded in the plea roll for 12 Chas II Trinity term to 13 Chas II Easter term (1660-1661), referring to CP 40/2732-2745, can be found in IND 1/6373, which give rotulet numbers of cases reaching judgment.

6.3 Calendars and indexes

Manuscript calendars of entries for medieval plea rolls, compiled in the seventeenth century, can be found in the Map and Large Document Reading Room at The National Archives. Click on the links in the table below for the catalogue descriptions.

| Reference | Regnal year range | Date range |

| IND 1/17114– IND 1/17115 | 1-18 Edward 1 | 1272-1290 |

| IND 1/17125 | John – Henry V | 1199-1422 |

| IND 1/17134 | 25-28 Edward 1 | 1296-1300 |

| IND 1/17167–IND 1/17168 | Edward 1 to 24 Henry VII | 1272-1509 |

| IND 1/17172 | 1-20 Edward II | 1272-1292 |

| IND 1/17174 | Edward IV and Philip and Mary | 1461-1558 |

An index to the recoveries in the plea rolls is in IND 1/17180-17182 covering Henry VIII to Elizabeth I.

7. Further reading

The Court of Common Pleas in fifteenth century England, Margaret Hastings

An introduction to English Legal History, J H Baker