Summary of activity

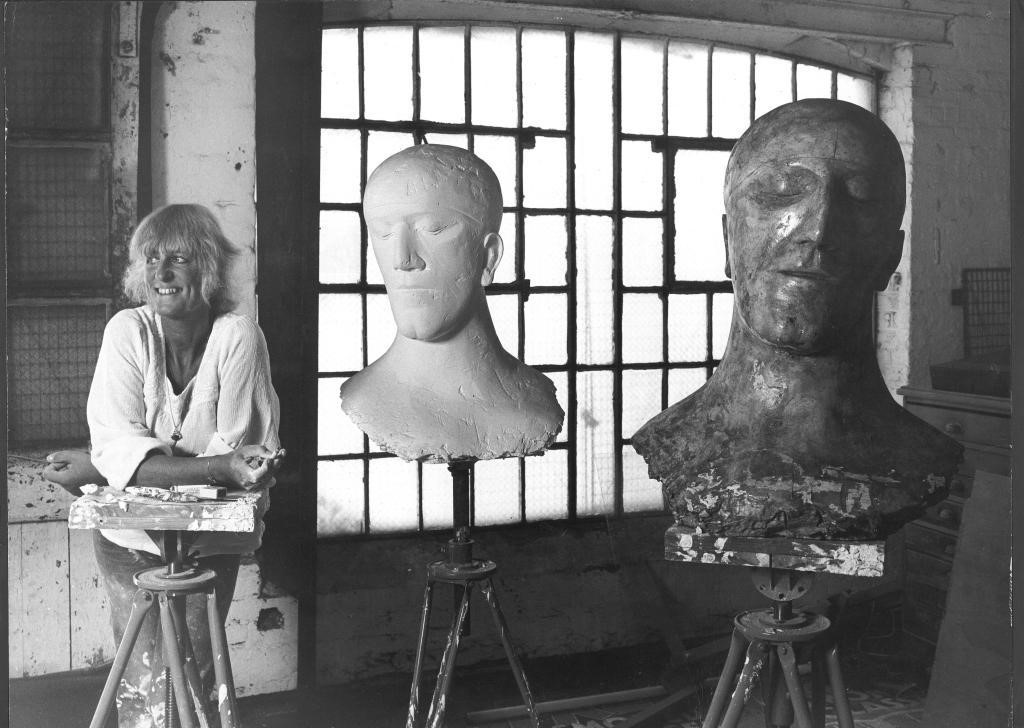

Dame Elisabeth Frink was one of Britain’s leading 20th century figurative sculptors. In 2018 the Frink archive was gifted to Dorset History Centre (DHC) following the death of her son, Lin Jammet. The acquisition of this prominent archive was a result of a long-term engagement and a building of trust with the family and the curator to the Frink Estate.

The archive contains photographs, correspondence, business records, printed material, works of art on paper, books, audio-visual items and other archival items that reflect the artist’s career. It is contained in over 100 boxes alongside ‘outsize’ materials which include a group of Frink sculptures and plaster maquettes.

Acquiring the archive has raised the profile of DHC within the council and wider art world. DHC are building on this profile to increase access to the collection and are now taking a proactive approach to archiving the arts of Dorset.

Image credit: Dorset History Centre, D-FRK/2/1/13/3/5

Challenges and opportunities

The key challenge for DHC was not knowing if the Frink archive would ultimately be gifted to them. Frink’s son, Lin, had expressed a preference for the archive to stay in Dorset. DHC were aware that trust needed to be built up and maintained a relationship with Lin for over 13 years. They worked with him and Annette Ratuszniak, (former curator of the Frink Estate) to prepare for the deposit of the collection.

Within that time some specific challenges emerged. This included clarifying what archives were held and what format they were in. DHC worked to identify items which would be of interest for accessioning and cataloguing. DHC prioritised business records and works of cultural content, such as preparatory sketches for sculptures. DHC knew that these records would be of interest to galleries, auction houses and researchers.

There were some sensitivities relating to copyright and these were approached on case-by-case basis. It was agreed that the archive would be a collection of all recorded information, not just the artistic output of Frink herself.

The archive included a number of large items, including the sculptures and plaster maquettes. DHC, decided contrary to its normal policy, to take the objects as there was a strong link to the archive collection. It was the first time DHC had acquired anything of this nature.

The high-profile collection opened up access to wider sources of funding. A grant from the Henry Moore Foundation and support from private philanthropy enabled the recruitment of a project archivist who was focused on cataloguing the collection. Unfortunately, Covid-19 interrupted progress of the cataloguing project. DHC were able to complete the catalogue by working closely with Annette and a range of part-time staff. The catalogue is now accessible through their website.

Outcomes for service users

The most obvious outcome is the use of the freely accessible catalogue of Frink’s work. There is no charge to access material on-site which means anyone interested in Frink can book to come and view parts of the archive. The extensive collection provides a rich source of information for researchers on Elisabeth Frink and her life as well as inspiration for students and contemporary artists. In addition, it also helps to demonstrate the importance of place, specifically Dorset, in her work.

The project has also had the benefit of raising the profile of artistic archive collections and DHC’s interest in preserving them as counterparts to the artists’ works.

The reach of the archive has been expanded through new relationships with a range of organisations notably Dorset Museum, the Ingram Collection, Yorkshire Sculpture Park and the Sainsbury Centre at the University of East Anglia. Jo Baring, Director of the Ingram Collection, produced a podcast on female sculptors which featured DHC and the Frink archive. Additionally, DHC has loaned items and provided content for two Frink-themed exhibitions at Messums Wiltshire.

DHC was a delivery partner in My Creative Life: Talking Heads, an exhibition of clay sculptures inspired by Elizabeth Frink at Dorset Museum. DHC’s contribution to the project centred on work with a group of young adults with mild to moderate learning disabilities in Weymouth. They worked with a clay artist to explore Elizabeth Frink’s Green Man drawings and make 3D heads. The power of the original Green Man drawings captivated participants and they were encouraged to explore their own personal responses to the works. DHC also made three simple activity films, for download and use by social care settings or individuals, one of which features a Green Man design recreated in salt dough.

Since acquiring the archive, other Frink-related material has been gifted or deposited at DHC. DHC welcomes enquiries from museums and galleries working on Frink-related projects in order that the archive can be utilised by a wide range of audiences.

Through the acquisition DHC have gained confidence in talking to others who may be considering donating their arts archive. They have developed an understanding of how to manage sensitive conversations and that playing the ‘long game’ in terms of acquisition is sometimes necessary. They have also found opportunities to raise the profile of other artists in their collections including Rena Gardiner, an illustrator, and Mary Spenser Watson, a sculptor.

What was learned from the process?

The key thing DHC learned from the process was the importance of relationship building and the time it takes. From the idea of DHC being a repository for the Frink archive to it being a reality took time, patience and commitment. Understanding the wishes of the family and the context within which they wanted the archive preserved was vitally important.

There were many sensitive negotiations which took place to assure the family that DHC was the right place for the archive. DHC had not acquired anything as big or as notable as this before and they do not anticipate acquiring a collection of this type again in the near future. However, they have learned skills from this process that they are already applying to discussions with living artists, their family members and estates.

DHC have stepped up their ambitions to acquire archives of other notable artists and have a guide on their website about their art, artists collections and their work in archiving the arts. Their Archiving the Arts introduction for potential depositors details what they are looking for and how to deposit artistic collections at DHC.

DHC also learned about the ecosystem of the art world, where the connections are and how positive they can be in supporting the process of archiving and collecting. DHC now has a better understanding of the worlds of sculpture and visual arts and is more confident in working within them. They are in contact with a range of organisations that hold and host Frink’s sculpture (e.g. Yorkshire Sculpture Park) and are looking to share the knowledge they have gained from cataloguing the collection.

Key advice

The advice DHC would give to anyone thinking of taking on a similar project is to have patience. With collections of this nature the overall process cannot be rushed. There is an emotional attachment to the items and it’s important to let the family members make up their own mind. There were a lot of private papers in the Frink collection and therefore her son had to really trust the people he was handing them over to. He needed to know they would be presented in a way that was aligned with his and his mothers’ values.

DHC are now building on the knowledge they have gained from the process of acquiring the Frink collection and are being proactive about seeking complementary collections. Archiving the Arts forms part of the collecting strategy of DHC. It is a means by which DHC hope to safeguard and preserve the important working papers of significant artists and cultural figures who live or have lived and worked in the county. DHC has identified artists (in the broadest sense) as a sector that could be much better represented within its collections. DHC’s interests are:

- Preservation: ensuring the long-term survival of important records

- Access: Making material available to researchers of all kinds

- Education and engagement: inspiring learning by working with collections.

How will this work be developed in the future?

DHC are keen to preserve more collections of significant artists and cultural figures to ensure that they become part of the county’s permanent historical record. This includes visual artists and photographers, writers, designers, theatre and dance practitioners and musicians as well as the organisations that support them – for example arts centres, development agencies and professional bodies.

A major capital project is being planned by DHC and the Frink collection, which is considered the jewel in the crown of DHC and will form a key part of the activity plans. DHC plan to use the broad range of arts archives they hold to engage and commission artists to open up DHC’s collections to a broader range of audiences.

They are planning to engage more children and young people by becoming an Artsmark Partner and working with Arts University Bournemouth on arts-based projects. DHC also plan to continue their partnership working with arts development companies, health and wellbeing providers, museums, and galleries.

Find out more about this case study by contacting Sam Johnston, Service Manager for Archives, Dorset History Centre