Main section

Tabs Navigation

Tabs

Active or inactive?

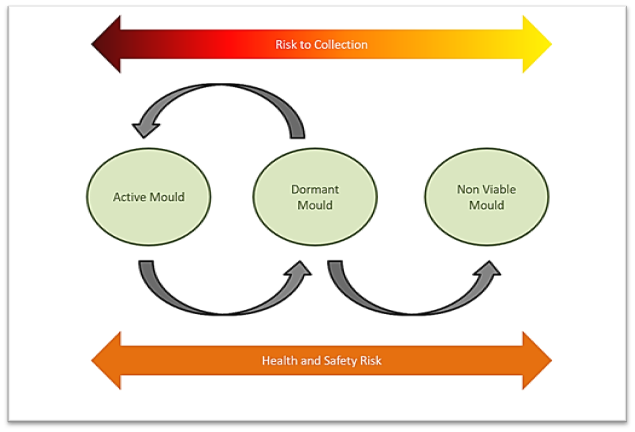

Mould exists in one of three states – it is actively growing, dormant, or non-viable (dead). While it is understood that active mould is hazardous to both the collection and those accessing it, it is also important to be aware that dormant and non-viable mould also present a risk to health (Fig. 1). The effects of exposure to mould are cumulative and around 2% of the population may develop an adverse reaction to it.

Mould lifecycle stages and risk, The National Archives

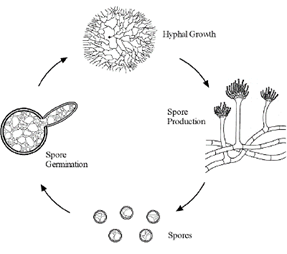

When growing and reproducing, mould requires an organic food source, like paper, parchment, adhesive and other materials found in archival collections. It also needs moisture and thrives when the surrounding environment has a sustained relative humidity (RH) of +65%. When such conditions occur, germination and growth begin. Microscopic spores – or conidia – are released into the air and as they land on a surface that can support growth, they germinate into hyphae. These thread-like cells release digestive enzymes which degrade and subsequently absorb nutrients from the food source and form the visible body of the fungus, known as a mycelium.

If disturbed by air movement or by physical contact, conidia are released into the surrounding area and, given the right environmental conditions, will go on to form further mould colonies.

When active mould growth is present, you may observe:

- A perceptible musty odour, both within a storage space and on a document itself

- A damp feel to the document surface

- Noticeable changes to the appearance and condition of the document

- Fluffy or slimy growths, which may smear when touched

Identifying and responding to an active mould infestation is essential. When left untreated, active mould can spread quickly, posing a risk to the ongoing condition of your wider collection, as well as to those who access it.

As humidity levels decrease, active mould becomes dormant and it:

- Desiccates, becoming dry, powdery, or crusty and – like active mould – can be disturbed by movement

- Can remain inactive for many years but may reactivate once humidity levels create a suitable environment

- Can appear as mottling or staining on the document surface, often with dry, powdery deposits in the box – though appearance can vary widely

Because you cannot visually assess the difference between dormant and non-viable mould, (Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) should always be worn whilst handling affected collection material.

What does mould look like?

Due to age, storage and usage, archive and library collections may be soiled and discoloured, making it difficult to tell the difference between mould growth and historic dirt deposits. As such, identification of mould is not always straightforward. However, there are several key characteristics to look out for which may indicate its presence within your collections.

Common visual indicators can include:

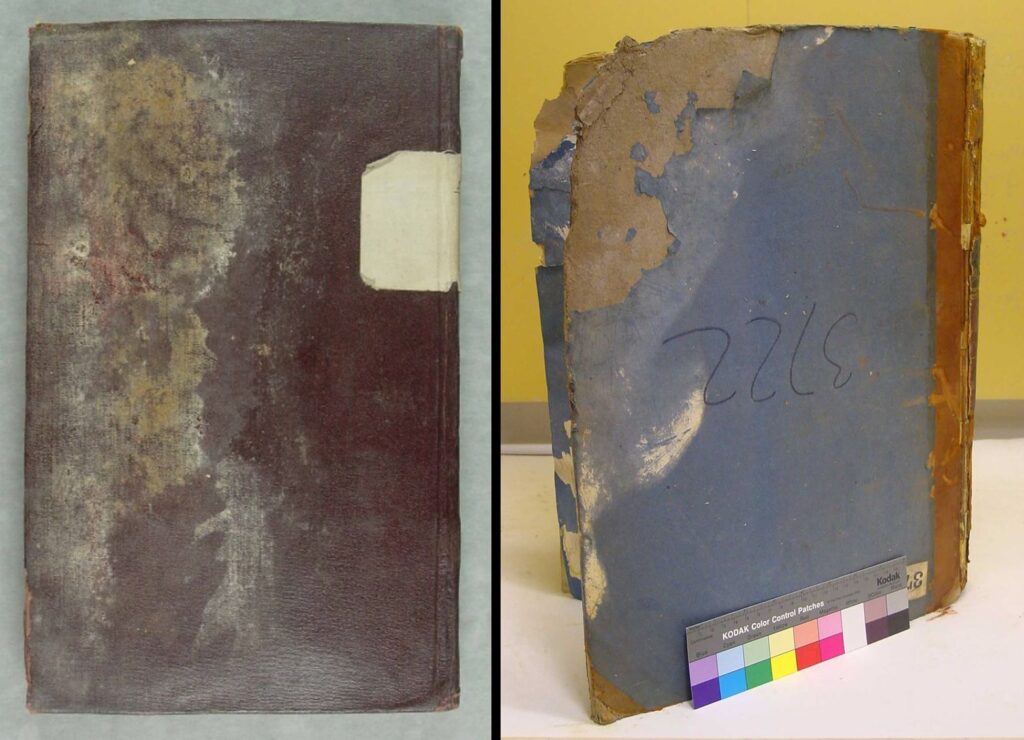

- Staining, mottling and/or discolouration of the affected surface, frequently in a circular pattern and in a variety of colours (Fig.2-4)

- Water damage and/or tide marks – where contact with moisture has occurred, mould growth is common (Fig. 5-6)

- Surface deposits – mould that is actively growing, or powdery accretions of dormant mould (Fig. 7-8)

Figure 2 – FO 277/215

Figure 3 – WO 78/4369

Figure 4 – E 190, piece number unknown

Figures 5 and 6 – IR 58/21229 and ADM 38/3722

Figure 7 – AO 3/877

Figure 8 – WO 78/4369

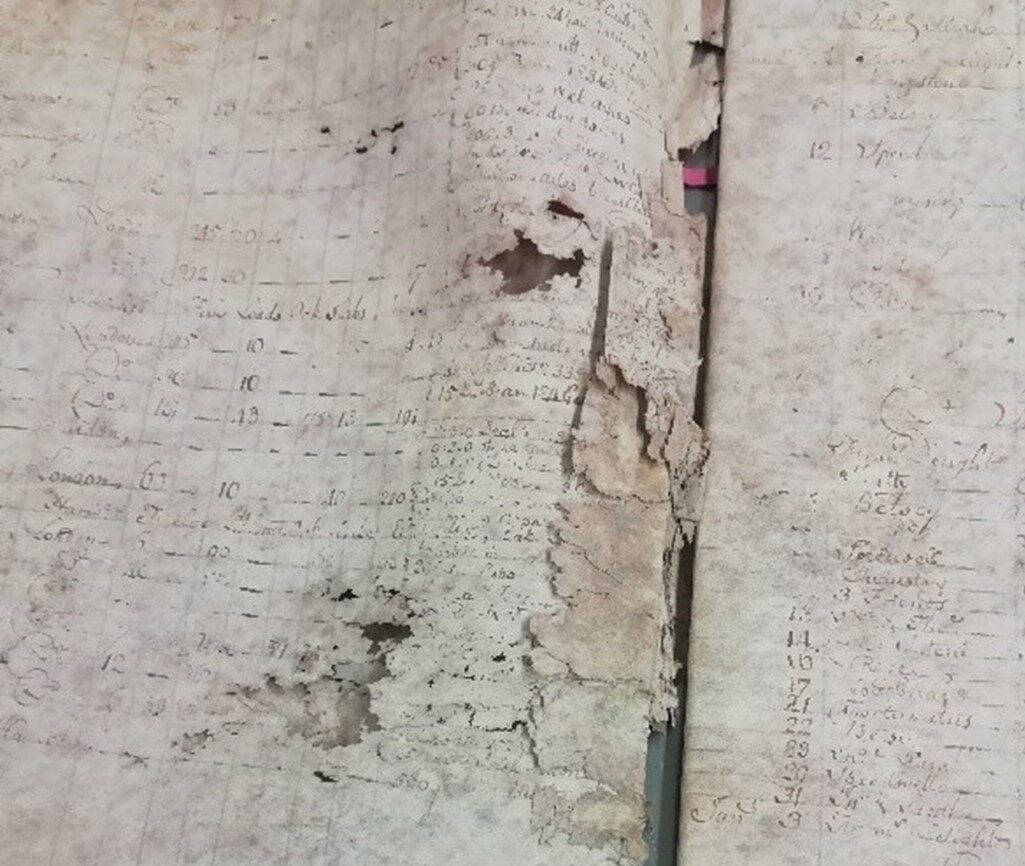

What does mould damage look like?

During mould growth, digestive enzymes cause weakening of the surface. This can impact significantly on the condition of a document and lead to irreversible damage, including:

- Adhesion and/or blocking – through the addition of moisture, pages are stuck together and cannot be turned or separated easily (fig. 9-10), leading to loss of information

- Breakdown in mechanical strength of substrate – a document becomes difficult to handle without causing further damage (fig. 11-12)

- Losses – where significant portions of a document have been detached or completely dissociated (fig. 13-14), leading to loss of information

Figure 9 – E 190/5/4

Figure 10 – E 190/5/4

Figure 11 – C 101/1246

Figure 12 – IR 58/21229

Figure 13 – SC 6/CHARLESI/1703/1705

Figure 14 – E 190/585/21

For further information on the ecology of mould, please refer to [hyperlink to Ecology of Mould pages]