Using and interpreting cartoon sources

Political cartoons can be found in the pages of nearly every newspaper in the world. Cartoons that have a message, cartoons that make people think and cartoons that make people laugh. They can give us a unique perspective on a particular event and throw light on public attitudes and values. Therefore, to understand a cartoon, we need to know its historical context:

- What was happening at the time?

- Who are the main people in the cartoon?

- Why are those people important/whom do they represent?

- What are the artist’s intentions?

A political cartoon about the introduction of Marshall Aid by Clive Uptton. Catalogue ref: INF 3/1295. President Truman signed the Economic Recovery Act of 1948. It was named the Marshall Plan, after Secretary of State George Marshall, who in 1947 proposed that the United States provide economic assistance to restore the economic infrastructure of post-war Europe.

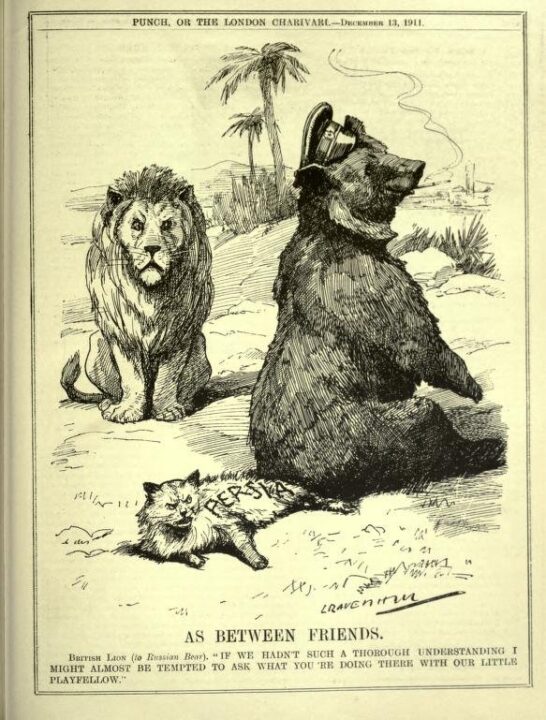

Cartoonists use a range of techniques which we need to learn to read. For example, the cartoonist might compare people or events in their cartoon to ‘symbols’ that no longer exist or make sense today. Symbols are pictures and images that are used to represent countries, people, events, and qualities. As well as ‘John Bull’, there are other symbols for Britain. Britain has been represented as a lion or by the figure of Britannia, a woman with a trident and dressed in Roman clothes. Symbols can be seen as shorthand for other things too. For example, a cart horse for the trade union movement or doves or lilies used to represent the idea of peace.

Cartoon by Leonard Raven-Hill from Punch Magazine, or The London Charivari. 13 December 1911. Title ‘As between friends.’ [Wikimedia Commons] Transcript: As Between Friends: British Lion (to Russian Bear): ‘If we hadn’t such a thorough understanding I might almost be tempted to ask what you‘re doing with our little playfellow’.

Famous people can also be recognised from a symbol. A cartoonist may exaggerate of one of their most prominent features or characteristics and turn it into a symbol for that person. A cartoonist in the Second World War just had to draw a toothbrush moustache and everyone would instantly know that it was meant to be Hitler. When people saw a fat cigar or the ‘V’ for Victory sign they automatically thought of Winston Churchill.

Cartoons also give us other visual clues. The way the cartoonist has chosen to draw important people infers what he/she thought about them. The situation shown or what appears in the background also gives us clues.

A cartoon usually consists of two elements, a drawing that pokes fun at an individual or event and something that is not real. Their subject is shown in this ‘made up’ situation enabling the cartoonist to make their point.

Politicians might be made to look ridiculous, or events and situations exaggerated to amuse. Cartoons can also shock. They might suggest things that people might be reluctant to say. Historical political cartoons rarely make us laugh loud as we are not viewing them as people of the time. What was considered witty twenty or hundred years ago may seem like a stale joke or completely lost on us today.

Why are cartoons useful as sources?

Cartoon for ‘Ditty Box’ magazine : Hitler appears as the organ-grinder and Mussolini the monkey , 1939-1946, Artist: Wyndham Robinson, Catalogue ref: INF 3/ 791R. The cartoon refers to Rudolf Hess, who was Hitler’s deputy from 1933. In 1941 he secretly flew to Britain on a mission to negotiate a peace between Britain and Germany. It is also critical of the wartime relationship between Germany and Italy. The term an ‘organ grinder’s monkey’ means that a person is doing what a powerful person wants them to do and have no real power themselves. Street organ grinders historically used monkeys to perform tricks and attract interest and money.

Value of cartoon sources

- They provide first-hand opinions of events and people, offering unique perspectives that can enrich our understanding of these concerns. They may show someone stronger or weaker to communicate a viewpoint. They often use satire and humour as part of their commentary.

- Cartoons are often created for a wide audience and mass consumption. Arguably they can reflect public opinion or specific political or social groups.

- They can also reveal different opinions about complicated issues, events or people in a more accessible way.

- They are helpful to use together with written sources to build a comprehensive interpretation of historical event.

- Cartoons often use visual imagery, symbols, and caricatures to convey messages. These visual elements can also capture the sense of an era and communicate ideas that might not be as effectively conveyed through other types of historical records.

- Some cartoons too, may be evidence of a government’s efforts to influence people in a particular way and could be seen as instruments of propaganda.

- Historians must be able to tell the difference between fact and opinion. Therefore, we must always try and place the cartoon in context. This means understanding the historical situation it is commenting upon, so we can evaluate its reliability as evidence.

- Historical cartoons can help to develop your visual literacy skills which is important for understanding today’s newspapers, magazines and webpages.

- Cartoons can help develop your critical and creative thinking.

Questions for cartoons

Looking

- Is there an original caption or title?

- What is happening in the picture?

- Can you identify the people/place/circumstances that the cartoon relates to?

- What techniques has the cartoonist used to make the cartoon persuasive? Has he/she succeeded?

- Do you have evidence in image of the date/period?

- Can you identify the cartoonist and research their work?

Understanding

- What is this cartoon about?

- Does this fit with your knowledge of the context of the cartoon?

- Can we detect the cartoonist’s point of view?

- Is the cartoon from a publication that has a particular political view?

- What could be another angle on the same issue?

- What other sources would help to understand this cartoon?

- Does this cartoon give us a perspective on a historical event that written documents may not?

Activity

Look at all the cartoons on this web page. Try and answer the questions. Remember you may need to research the historical context if you are unfamiliar with it.

Printable worksheets

Cartoon recording sheet

Download cartoon recording sheet – Word document

Download example cartoon recording sheet (filled in) – Word document

Download cartoon recording sheet – PDF

Cartoons suggested activities

Download cartoons suggested activities – Word document